The politician's major care: his own future

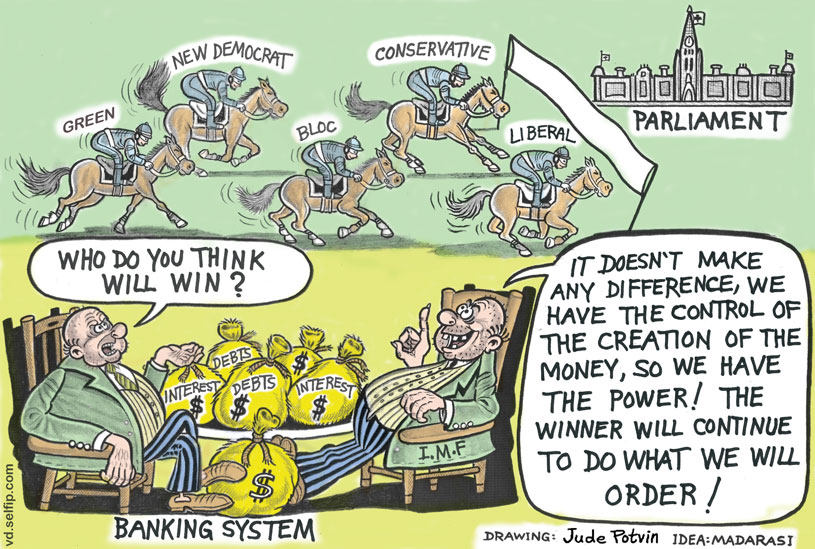

The recent elections in Canada have left the electors more disillusioned and cynical than ever: over 40% of them did not bother to vote, feeling that their votes would not change anything to improve the situation of our country, that none of the running candidates offered real solutions, that their promises are not to be believed, or simply, that those who actually run our country are not elected — the people we elect are just their puppets. It is true that during this campaign, the leaders spent most of their time throwing dirt at each other, instead of explaining their own platform, which certainly did not help the electors to make an enlightened choice.

If, for many Canadians, elections are not important, the situation is entirely different for the politicians: it is their jobs, their future that is at stake. The Canadian political parties seating in the House of Commons even agreed to vote a law that gives any party $1.75 per vote it receives on election day. No wonder they go to great lengths to get people to vote! Here is what Mr. Even wrote about these politicians, which summarizes the position of our Movement regarding political parties:

For the politicians, election time is the big event of the year. But is it an event of capital importance for the people? How can it be? It is not the people who are being voted for; the people are not the candidate or candidates. The people do not present a program, especially considering that they haven't the faintest notion how to prepare one or present it. If there is a question of a program, it is usually left to the humbugs who occupy the election platform.

For MPs who are emerging from the dissolution of Parliament to become candidates once more, and for the new candidates, the great, the prime, the unique question in their lives is: their own immediate political future. Their own future, first of all. Then the future of their party. As for the future of the country, the people and families — they couldn't care less! They have become quite used to ignoring such matters without losing any sleep nor experiencing any fall-off in appetite.

Oh, these ladies and gentlemen will certainly visit the people! More than they did during the three preceding years taken together. But not with the aim of trying to find out what the desires of the people are. They are going to the people, driven by what they themselves want so badly. They are not going to the people to bring them any favours. They are going to demand favours of the people for themselves. (Editor's note: the recent sponsorship scandal just confirms this.)

The politician is not a man who gives something, much less a man who might possibly give himself. He is a man who takes, and takes more and more as long as he possibly can. And if he could have his way, his outstretched hand would still be grasping as they carried him to the grave.

So the honourable member claims to represent his electors? How does he prove it? How many times, during his term in office, does he go to his electors to ask them what they wish, what public measures they expect from Parliament, in order that he may return to the House of Commons and present their demands to Parliament? Even during his electoral campaign, when, as a candidate, he meets his constituents in some assembly, does the candidate ask these constituents to express their desires? Does he not rather spend the time telling them what he wants, repeating his desire — their votes — insisting that they cast their ballots for him on election day?

We have been told, and in all solemnity, that election time has for its object to allow the people to pass judgment on those who have represented them, or on those who wish to represent them. But take a good look at a typical election campaign assembly; watch those who are presenting themselves and those to whom they are presenting themselves. The scene is hardly reminiscent of a judgment hall. Those who are supposed to be judging are seated down on the floor, while the judged strides the platform above, perorating at great length, and hardly wearing the look of someone who has come to have judgment passed on him.

And such are hardly the type who could be held up as models of humility nor modesty. Nor could they be said to be disinterested. He becomes in fact a consumate actor; he portrays, not the man he is, but the man he wants the electors to believe he is. What is important is not what you are, but what the people think you are. He neglects no art or artifice to persuade the electors that he is the only man worthy of being returned to the House of Commons.

But one thing cannot be dissimulated by the candidate: a point which keeps coming to the fore time and time again, especially as the great day draws nearer, and that is the object of the election campaign: to be elected. He will tell you with the look of a martyr that the office of representative of the people is a heavy one, charged with onerous responsibilities, and requiring many personal sacrifices. But somehow or other he manages to bear up under these heavy duties and these sacrifices. And nothing can cause him greater grief than to be sent back home the day the votes are counted.

How many words are spoken, and how much print is used in an endeavour to persuade the people to continue to place prime importance in the farce which is acted out by these mountebanks!

Certainly the Pilgrims of St. Michael, and all those who usually read our pages, are under no illusion with regard to the real worth of these characters.

It is of very little importance that this actor A, or actor B, or C or D should win the election over the other three. What is important is that citizens should stop thinking that they have fulfilled their civic responsibilities when, once every four years, they hide themselves behind a curtain in a little booth and mark a cross in pencil at the end of a name on a piece of paper. What is important is that citizens should learn to shoulder their responsibilities the year round.

What counts is that the citizen takes the necessary steps to inform himself. Citizens must learn that their essential needs and fundamental aspirations are the same; that political division in no way corresponds to these needs, and that such a division only results in weakening the strength of the people, and is surely the most efficacious means of keeping them under what is virtual bondage.

What is important is that the citizens should learn how to unite in order to obtain, together, a system of service in place of a system of demands and exactions; to obtain the abolition of the purely financial obstacles which stand between the immense productive capacity of the country and the fulfillment of such needs.

Men and women who are devoted to the service of carrying the message of education and union are infinitely more valuable to the country than are these egoists who are consumed with a passion for publicity, renown and money; who strut and stride before the people — a people whom they cajole and persuade in order to have their votes, and after their votes, their money — but a people who are very soon forgotten and betrayed.