Pope Francis: Listening to what the other tells me

and saying what I think, with kindness

The Holy Year of Mercy has just ended. What do we remember of this year whose theme was “Be merciful as your Father is merciful”? There are two major points to remember: First, we must forgive those who have offended us, as we pray in the Our Father. Second, since the word “mercy” comes from the Latin “miseria” (misery, misfortune) and “cor” (heart), to practice mercy means to “open our heart to the misfortune and to the misery of others”, to bring our heart closer to our neighbor’s misery. In practice, this can be done by partaking in works of mercy of which there are two types: corporal and spiritual.

The Holy Year of Mercy has just ended. What do we remember of this year whose theme was “Be merciful as your Father is merciful”? There are two major points to remember: First, we must forgive those who have offended us, as we pray in the Our Father. Second, since the word “mercy” comes from the Latin “miseria” (misery, misfortune) and “cor” (heart), to practice mercy means to “open our heart to the misfortune and to the misery of others”, to bring our heart closer to our neighbor’s misery. In practice, this can be done by partaking in works of mercy of which there are two types: corporal and spiritual.

These works of mercy consist of simple acts of everyday life, but Pope Francis mentioned that if they were put into practice by every Christian, the face of the earth would be changed. The works of corporal mercy are better known, since they are taken from the Beatitudes of the Gospel: to feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, clothe the naked, welcome the stranger, heal the sick, visit the imprisoned, and another work of mercy was added: to bury the dead.

The spiritual works of mercy are less known but are just as important: To instruct the ignorant, to counsel the doubtful, to admonish sinners, to bear wrongs patiently, to forgive offences willingly, to comfort the afflicted, to pray for the living and the dead.

To bear wrongs patiently means that we must be patient towards our neighbor, the way God is patient with us. In everyday life, this applies above all to dialogue: When we speak with someone, we often have the tendency to interrupt or even to prevent someone from saying what he wanted to say, when we see that he does not share our point of view. This is often the cause of many misunderstandings that can turn into resentment, into conflicts, even into open warfare between individuals, between members of a family, at our workplace, or even between countries.

Dialogue was central to the lecture Pope Francis gave in Saint Peter’s Square Saturday, October 22, 2016. Following are the Holy Father’s words offered to your meditation… and to be put into practice!

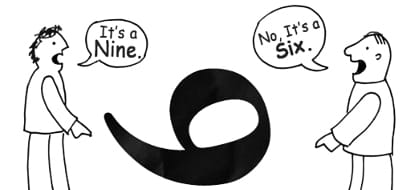

Our vision of things depends on our point of view: before we say that the other is wrong, we must listen to his arguments, that is, put ourself in his place in order to understand his point of view.... Our vision of things depends on our point of view: before we say that the other is wrong, we must listen to his arguments, that is, put ourself in his place in order to understand his point of view.... |

Dear Brothers and Sisters, Good morning!

The passage of John’s Gospel that we heard (cf. 4:6-15) recounts Jesus’ encounter with a Samaritan woman. What is striking about this encounter is the very succinct dialogue between the woman and Jesus. This allows us today to underline a very important aspect of mercy, which is dialogue.

Dialogue allows people to know and understand one another’s needs. Above all, it is a sign of great respect, because it puts the person into a stance of listening, and into a condition of being receptive to the speaker’s best viewpoints. Secondly, dialogue is an expression of charity because, while not ignoring differences, it can help us investigate and share the common good. Moreover, dialogue invites us to place ourselves before the other, seeing him or her as a gift of God, and as someone who calls upon us and asks to be acknowledged.

Many times, we do not encounter our brothers and sisters, even when living beside them, especially when we give precedence to our position over that of the other. We do not dialogue when we do not listen well enough, or when we tend to interrupt the other person in order to show that we are right.

However, how many times, how many times as we are listening to a person, do we stop them and say: “No! No! It isn’t so!”, and we do not allow the person to finish explaining what they want to say. And this hinders dialogue: this is aggression. True dialogue, instead, requires moments of silence in which to understand the extraordinary gift of God’s presence in a brother or sister.

Dear brothers and sisters, dialogue helps people to humanize relationships and to overcome misunderstandings. There is great need for dialogue in our families, and how much more easily issues would be resolved if we learned to listen to each other! This is how it is in the relationship between husband and wife, between parents and children. How much help can also come through dialogue between teachers and their pupils, or between managers and workers, in order to identify the most important demands of the work.

The Church, too, lives by dialoguing with men and women of every era, in order to understand the needs that are in the heart of every person, and to contribute to the fulfillment of the common good. Let us think of the great gift of creation, and the responsibility we all have of safeguarding our common home: dialogue on such a central theme is an unavoidable necessity. Let us think of dialogue among religions in order to discover the profound truth of their mission in the midst of men and women, and to contribute to the building of peace and of a network of respect and fraternity (cf. Encyclical Laudato Si, n. 201).

To conclude, all forms of dialogue are expressions of our great need for the love of God, who reaches out to everyone, and places in everyone a seed of his goodness, so that it may cooperate in his creative work. Dialogue breaks down the walls of division and misunderstandings: it builds bridges of communication, and it does not allow anyone to isolate themselves, or withdraw into their own little world.

Do not forget: dialogue means listening to what the other tells me, and saying what I think, with kindness. If things proceed in this way, the family, the neighbourhood, the workplace will be better. However, if I do not allow the other to say everything that is in his heart, and I begin to shout — today we shout a lot — this relationship between us will not thrive; the relationship between husband and wife, between parents and children, will not thrive. Listen, explain, with kindness; do not bark at the other, do not shout, but have an open heart.

Jesus understood well what was in the heart of the Samaritan woman, who was a great sinner: nonetheless, he did not deny her the opportunity to explain herself; he allowed her to speak to the end, and entered little by little into the mystery of her life. This lesson also applies to us. Through dialogue, we can make the signs of God’s mercy grow, and make them an instrument of welcome and respect.

Pope Francis