Mary of Australia

St. Mary MacKillop (1842-1909)

Beginnings

|

| Mary Mackillop at 33 years old |

Mary was born on January 15th, 1842 during a time of great spiritual upheaval. The Stephens Act of 1872 was ruining the lives of Catholics in Australia through the system of education. Mary’s life was spent in the battle for the establishment of true Catholic schools and other charitable institutions in Australia. Her nuns are still carrying out her mission today, not only in Australia but in different countries around the world.`

Mary’s parents were born in Lochaber, Scotland. Her father, Alexander MacKillop, was an educated and energetic man who defended his faith against the often anti-Catholic sentiments of the day. Although he was a good man at heart, Alexander’s financial situation was often very unstable. This caused much grief among the family members and often left his family to be supported by their relatives. As a result of the family’s financial crisis Mary was compelled to work at a young age.

Mary’s first position was that of governess for family members and because of their large families she was able to help them in raising their children. These experiences served her well in later years when she would become a teacher for Australian youth. Her older sister Annie said this about her; "She was a very wise and beautiful child. People often stopped her nurse just to look at her; she was so like pictures of angels. She had a wonderful memory and was always old for her years. One day when she was walking with her mother, Mary being then four years old, her mother complained of being tired and Mary offered her arm to help her."

When the family’s financial situation was more stable, Mary attended a private school with her brothers and sisters. This did not last long because of their father’s financial difficulties, but even so Mary’s education was of the highest quality. This is believed to be because her father undertook much of her education himself.

Mary had a very remarkable manner of self-expression. She was especially gifted with the spoken word, and this is evidenced in the many letters she wrote during her life. Her deep knowledge of the Catholic faith with its traditions and history and her ability to deal with delicate and difficult subjects, all served to make Mary an unusually educated woman. She inherited some of her father’s fighting temperament. Her sister Annie notes that one day when Mary was eleven years old, she sent home a drunken servant-woman who was supposed to be nursing her baby brother.

|

|

|

Fr. Julian Woods |

Mary was employed as a governess in Penola, Australia at the age of eighteen. It was there that she met Fr. Julian Woods for the first time. He was to be instrumental in the foundation of the Institute of St. Joseph. She also became sacristan for the first time in the little church there and this particular employment was to be her joy throughout her life.

Mary’s life was very quiet and retiring during her years as governess. "One great happiness I enjoy is being able to visit the chapel at any time, where the Blessed Sacrament always is…" she said.

In 1866, Mary established a small convent for herself and two other women in Penola. It was there that she was first called "Sister Mary." Two of the rooms of the house were used for the school so it was very crowded, but with the help of Fr. Woods, a larger building was soon given to the new congregation.

|

|

|

The convent at Penola |

After organizing the convent in Penola, Mary traveled to Adelaide in 1867 to establish a house there. Although the sisters began with sixty students, within six months’ time they had over two hundred attending the school.

Mary took religious vows on August 15th, 1867. She chose the name Sister Mary of the Cross. The Rule for the new order was written by Fr. Julian Woods.

Secularism in Australia

From the 1830s to the 1880s the school system in Australia was under great strain. The secularists were systemically taking over the building and running of schools to the dismay of the Catholic population. Many people were favouring the State schools because one could obtain grants for students, as such they were more practical for the impoverished families.

The Stephens Act of 1872 stated: "In a couple of generations, through the missionary influence of the State schools, a new body of State doctrine and theology will grow up, and the cultured and intellectual Victorians of the future will directly worship in common at the shrines of one neutral-tinted deity, sanctioned by the State department." Henry Parkes, the New South Wales Premier, stated that with the secularisation of the schools he held in his hands "what will be the death to the calling of the priesthood of Rome."

The secularists of the 1800s were working for the same goal as the secularists today. Archbishop Vaughn said that the secularist society would destroy the Catholic Church in Australia.

In their Joint Pastoral letter of 1879, the Catholic bishops issued a statement saying; "The Church knows that instruction is not education, and that a system of national training from which Christianity is banished is a system of practical paganism, which leads to corruption of morals and loss of faith, to national effeminacy and to national dishonour. We prize above all imaginable things, the Faith of our Fathers; that Faith is in peril in a great measure on account of the menacing condition of modern society; and cost what it may, it must be preserved and fostered in the hearts and intellects of the rising generation."

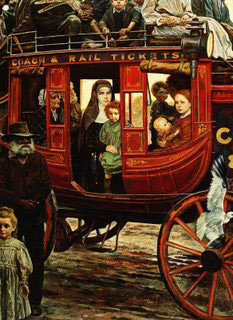

Catholic education was experiencing a downward spiral because of the shortage of priests and nuns who were willing to travel through the rough outback as well. Often the roads were only a deep rut, and travel by stagecoach was very difficult. The only practical method of transportation was by horseback.

Because of these difficult situations, the work of Mary and her nuns were very much supported by Bishop Vaughn. He knew that the Catholic faithful needed good teachers to bring them up in the practice of their faith.

In 1873, Mary wrote to Rome to request support in her mission. She commented as well on the lack of religious personnel in the teaching field. She made a point of speaking about the indifference of the secular governments towards the Catholic poor, and reiterated that the secularists were a danger to the Catholic society at large.

Difficulties and expansion of the order

|

|

|

Artwork depiciting Mary during her travels |

Mary Mackillop knew very quickly in her life that nothing advanced spiritually without trials and that was especially true of those who followed the Cross. She often told Fr. Woods that it is not a good thing to allow others to think badly of you unjustly (and thus give yourself a heavier cross to carry), especially when these people become disturbed because of what they believe about you. "Humility in its truest form," she said, "demands that you tell them the truth. It is not right to not do this just to keep that Cross for yourself."

Mary left for Brisbane in December of 1869, leaving seventy-two nuns in Adelaide directing twenty-one schools, an orphanage and a home for the aged.

Mary’s sisters remembered her as kind and thoughtful towards others, and she was always gentle and humble when she had to admonish any of them. Her inner peace and trust in divine providence were traits that everyone noted and admired.

Mary established a Refuge in Brisbane for women who were just coming out of prison or who were on the streets. She also founded a home for the elderly, the incurably ill and those with habits such as drinking that made it impossible for them to live in society. These institutions were kept by the nuns who were aided by young girls who "had, in one way or another, made a false step, and wished to place themselves under the care of the Sisters." These young ladies had their own Rule of Life and were called Magdalens.

During these early days of the Institute, Bishop Sheil from Adelaide gave support to the sisters by expressing his happiness at the success of their work. However, there were many other Catholics who were critical of the Josephites.

Some of the clergy had negative opinions as well, among them a certain Fr. Haron, who was a close adviser to the bishop. The newspapers where controlled by the secularists, and advocated the opinions of the State and the enemies of the Church. They used the clergy’s murmuring to aid the cause against Catholicism. The clergy had complaints against Fr. Woods most of all and a few even made threats to the bishop that they would leave the diocese.

During this time two of the Sisters threatened the future of the order with alleged visions and apparitions. Mary and Fr. Woods’ opinions differed dramatically regarding these phenomena. Fr. Woods believed in the authenticity of the nun’s visions but Mary had serious doubts. This put a strain on their collaboration in the future of the order and created many problems of morale among the other sisters. Mary was very upset by these developments but continued to have faith in God. "There are times," she said to herself, "when the thought of God’s immense love and patient mercy come before me with a force that I cannot describe."

The two sisters, Angela and Ignatius, eventually confessed their complicity. This was not before they caused much grief to both the community and to Mary, however. They would create scenes of confusion, saying they had been visited by phantoms or had seen demons. Among the other occurrences there was the disappearance of the Blessed Sacrament from the tabernacle in the convent chapel.

Another obstacle that Mary had to overcome during this time was in the person of a Dr. Cani. He was the Vicar General and representative of the bishop, who advocated the Government grants that were issued for education. These grants from the Government came with strings attached, namely that all textbooks had to be standardized and that religious education was restricted to a bare minimum. In Brisbane the diocese was used to accepting these grants, with the compromises that came with them. Mary’s refusal to compromise on this issue infuriated her superiors, but she would not budge, saying that "clinging to duty could possibly have unpleasant consequences." Fr. Woods gave his full support to Mary on this subject.

Mary wrote to Dr. Cani, "My position as Guardian of our Holy Rule enforces this (decision) and in the presence of God I must say what the voice of conscience and duty dictate. It is impossible for us to become in any way connected with Government and be true to the spirit as well as the letter of our Rule."

Despite this opposition the Josephites founded three schools in Brisbane within only three months of their arrival. They wished to build a Refuge in Brisbane also but this request was ignored by the religious authorities, so the nuns welcomed all those who were in need in the convent itself.

By the year 1870, Fr. Wood’s health was fading, both mentally and physically. His erratic behaviour continued to draw much criticism from his fellow clergymen, which did not favour the work of the Institute in the eyes of the bishop.

|

"Let us refuse nothing to God’s love. He humbled Himself and suffered for us–let us be glad to show Him we are willing to suffer whatever He deigns to ask of us." – Mother Mary MacKillop |

Excommunication

In the beginning of 1871, Bishop Sheil returned to Adelaide after being in Rome for a year and a half in absence from his diocese. Due to the criticism of his priests and the adverse influence of Fr. Charles Haron, he started to take steps to force the Sisters to abandon their Director’s leadership and their own Rule.

Mary was traveling in other parts of the country but upon returning to Adelaide, she saw just how much ridicule her sisters were being subjected to by the local clergy. She wrote to the Bishop several times, stating that if he changed the Rule, she would not remain in the Institute but try to live the Rule elsewhere. Although she said, he had every right to change the Rule; her responsibilities were first to God.

The bishop and Fr. Haron started an examination of the sisters, above all testing them for their "competence" in teaching. The questioning was so distressing that many of the sisters protested as to the validity of the proceedings. After these examinations most of the sisters were stripped of their status and removed from the convent. Many of them refused to accept the new Rule proposed by the bishop and were dismissed from the Institute.

Matters climaxed with a formal excommunication of Sister Mary by Bishop Sheil in the chapel of the convent. All the charges against her were completely false but Mary remained calm and serene throughout the ordeal.

She later wrote: "I really felt like one in a dream. I seemed not to realize the presence of the Bishop and priests; I know I did not see them; but I felt, oh, such a love for their office, a love, a sort of reverence for the very sentence which I then knew was being in full force passed upon me. I do not know how to describe the feeling, but I was intensely happy and felt nearer to God than I had ever felt before. The sensation of the calm beautiful presence of God I shall never forget."

Several priests supported Mary, recognizing that she had been accused without just cause, but it was very risky for them to oppose the bishop. Many of these priests and religious were ridiculed because of their defence of her. In Mary’s opinion however, great trials meant the event of a great work and suffering must always precede victory. She never criticized those who persecuted her, preferring to think of them as instruments of God’s providence.

During this time Sisters Angela and Ignatius admitted their guilt in fabricating the apparitions and visions, admitting that the phenomena had been contrived. This admission greatly aided the cause of the sisters and improved the opinion of the clergy in Adelaide.

Soon after that Bishop Sheil became very ill. Fr. Haron had taken advantage of his poor health for years in order to further his own designs and had created much havoc in the Church. Bishop Sheil realized too late that his close administrator and adviser had deceived him. He said, "I am dying with a broken heart. Those whom I trusted contracted bad habits. At times I acted at their suggestions – I’m sorry."

The excommunication was lifted at the request of the dying bishop and Mary and her entire community were reinstated into their community on March 19th, 1871.

Commission Inquiry

The upheaval caused by this controversy prompted Rome to hold an inquiry as to the events surrounding the Institute of St. Joseph. Cardinal Barnabo sent a group of representatives from Rome to form a commission to study the case and question all those involved. The main subjects they reviewed were the events surrounding the apparition phenomena and the capability of the sisters to teach.

The final outcome was the complete exoneration of the sisters of all the charges against them and the replacement of Fr. Woods as director by Fr. Tappeiner. Fr. Wood’s instability and disobedience to Church authority was considered a hindrance to the expansion of the Institute. The commission was confidant that without him, the Sister’s would continue their work more efficiently.

Fr. Haron was recalled back to his monastery for the part he had played in deceiving his bishop and for the manner in which he had treated Fr. Woods and the sisters. The commission informed him that he was instrumental in causing grievous scandal and discord in the Church.

Journey to Europe

Due to the pressure put on the Institute by all these events, it was decided that Mary should go to Rome and plead for the Rule to be approved by the Pope. So on March 28th, 1873, she left Adelaide. Upon arrival in Rome, Mary wasted no time making contact with several bishops and priests who were to aid her in the advancement of her Institute in the years to come.

On August 1st, she left for her England with the knowledge that Rome would supervise the structures of the Rule and continue its progression to completion. Mary’s visit left a very good impression of the integrity of her character on the authorities of the Vatican.

During her travels across England and Scotland, Mary asked for prayers for her community and begged for donations to help finance the foundation of the buildings. Her inspection of different schools and convents taught her a great deal and it was her intention to use this knowledge upon her return to Adelaide. Another goal for this European trip was to recruit nuns and priests for Australia.

In 1874, Mary returned once again to Rome hoping to secure the Rule before her return, but further delays made this impossible. Mary wished to have all opinions on her Institute studied, so she decided to wait. Especially, the issue of multiple novitiates was a cause of deep concern for her. During the early days they had many problems of novices being sent out without proper training and she was loath to repeat the experience. She requested that a single novitiate be established to eliminate this problem.

Before she left Rome, Mary was given a revised Rule by the Propaganda for the Faith to be tested by the Institute on its feasibility in practical circumstances. Mary’s request for a novitiate at the mother house was granted and the new Rule stressed the need for proper formation of the sisters. Certain safeguards were also made in regards to the changes that a bishop could make either to the Rule or on how much authority they held over the superiors of the Institute. With much gratitude for the blessings her Institute had received, she left for the long return voyage to Australia on October 31st.

The Quinn brothers and Mary

During the mid-1870s, Mary came into conflict with two bishops. James and Matthew Quinn both opposed the Constitution of the Institute. They said that they, as bishops of their respective dioceses, should have higher authority over the Rule and the sisters.

Because the structure of the community had been directly ordered by the Holy See, Mary was not prepared to make compromises. As Mother General she was also obligated to observe strict obedience to Rome. Despite this, the Quinn brothers gave her a most difficult time. She knew what she had to do but her problem was preserving the respect for the office of the bishops, all while maintaining her position towards Rome.

Eventually they were told by their superiors in the Vatican that they did not have total jurisdiction over the convents in their dioceses. And so Mary was able to continue her work with the Institute without further opposition from them.

Even in these most difficult circumstances, Mary was full of strength – her wisdom, fortitude, patience, humility and charity were to be remembered by all with whom she served.

Mother Mary’s health

Mary suffered from a chronic illness called dysmenorrhoea. She carried this disease with her through most of her life although only a few of her acquaintances knew of this, because of her innate modesty. She would tell people, even her relatives, "I cannot enter into the particulars."

In those days, this illness was treated by a teaspoon of brandy that was administered during the high point of the pain. Mary was so strict in the administration of even such a small dose of the liqueur that she would order one of her sisters to give it to her. This was due largely to the slander that the press enjoyed so much to indulge in. She wrote about the shame and humiliation that this caused her, saying: "God knows that I was kept up by such when I should otherwise have sunk and not been able to do my duty."

Her illness was often so severe that her doctors would tell her to rest and stop all work. Of course, the exhaustion brought on by overwork, fatigue, anxiety over difficult situations and disappointments did not aid her in her general health. In a letter to her mother she wrote: "The illnesses you know of try me terribly. The doctor orders quiet and freedom from care."

|

"See how the work of Teresa was persecuted, how she and St. John of the Cross suffered, and oh, ever so many more... Our many trials have done us great good and serve to strengthen us." – Mother Mary MacKillop |

1883 – A great trial for Mary

Another great trial was in store for Mary, this time from an unexpected source. Bishop Augustine Reynolds at first supported Mary in the promotion of the Institute. However his mind soon became poisoned against her by her enemies, two among them being Archdeacon Russell and Fr. Polk. Fr. Polk succeeded Fr. Tappeiner after his death in the spiritual direction of the Josephite sisters. This caused much grief to the sisters because Fr. Polk was a harsh and exacting superior and confessor. Many of the sisters were afraid to even ask him for spiritual advice.

With the advice and criticism supplied by Russell and Fr. Polk, the bishop became so prejudiced against Mary that he summoned a commission to delve into these suggested notions of her misconduct.

The commission was totally controlled and supported by Mary’s opponents, so without looking at any facts in the case or allowing the sisters to defend themselves, the commission found her guilty of many different charges. This, although not a formal declaration, caused much sorrow to Mary because she knew that the testimony was falsely contrived.

Bishop Reynolds accused her in his letter of November 13th, 1883 of being a drunkard, violating her vows of religious poverty, of allowing the debts of the convent to become excessive and all manner of false testimony. The bishop decided to banish her to Sydney to found a new convent there, far from the diocese of Adelaide.

Mary’s answer to her bishop is a lesson to all of us in humility and obedience, considering the injustice that she was suffering. "The instructions in your last letter surprised me but I submit. All is, I hope, for the best – at least, I know you so intend it. I have made all the haste possible and will leave by Penola tomorrow. I can say no more, but grieving deeply for having caused you any sorrow, I remain your humble child in Jesus, Mary and Joseph." – Mary of the Cross.

A new home in Sydney

Mary’s letter to her sisters upon her departure for Sydney was full of hope and encouragement. "The Institute is passing through a severe trial but with humility, charity and truth on the part of its members all will in the end be well. Have patience, my own loved children, – pray – pray humbly and with confidence and fear nothing. Our good God is proving His work."

"We have had much sorrow and are still suffering its effects, but sorrow or trial lovingly submitted to does not prevent our being happy – it rather purifies the happiness." She warned her sisters to maintain a loving respect for the bishop and to blame instead those who misled him.

On December 17th, Mary sent another letter to her sisters telling them of the new Mother House in North Sydney. This is the site where Mary’s body is buried and many pilgrims go to venerate her. Most recently Pope Benedict XVI during his visit to Australia for the World Youth Day.

While in Adelaide the problems with Bishop Reynolds continued, Mary found a close friend and adviser in the person of Archbishop Patrick Moran. His support during the battle between Reynolds and the Institute proved to be invaluable, largely because of his visits to Rome in 1885 and 1888. He brought a complete report to Rome with him stating the events that had taken place, as well as many letters attesting to the good character of Mother Mary.

In February on 1886, Mary admitted to one of her sisters in a letter: "I now feel the effects of years of care and anxiety. It seemed only to require this quarrel with a Bishop I loved to make me almost completely break down. I say almost for I am trying hard for my Sisters’ sake to keep up, but there are times when the effort is too much for me and I break down and am quite helpless. It is so hard to know that many faithful children are suffering and that my hands are tied and I cannot help them, oh, it is very hard."

"There is no Order in the Church doing any good that has not been so tried, and often by some of God’s greatest servants. See how the work of Teresa was persecuted, how she and St. John of the Cross suffered, and oh, ever so many more... Our many trials have done us great good and serve to strengthen us."

When Bishop Moran went to Rome in 1888 he was given the final decision regarding the Institute of St. Joseph. The chief concern was the issue of central government and this was granted at last after many years of debate and suffering.

The documents were signed on July 25th, 1888, by Cardinal Simeoni and the Secretary to the Holy See.

During the following years Mary supervised the foundation of new houses in many places in the continent of Australia. Her health continued to fail steadily and the difficulties of maintaining the Institute and the constant travel and hard work augmented the serious illness that was always with her.

In a letter to Mother Bernard, she mentions: "Another thing dear Mother, that I must ask you to remember – I have had a very heavy strain on me and am now feeling the effects of it. Was very seriously ill in Adelaide, and just one week after I was better, got very bad again – so bad that I had to keep as quiet as possible, in pain and misery for another week. Owing to your fears – and wicked minds (of the media) – I could not take the remedy that would have done me good, so that I lost a week of valuable time."

Mary continued to travel extensively, spending almost three years in New Zealand founding convents, orphanages, shelters for the neglected and unwanted. These three years were among the happiest of her life, and she was often to say after: "I like New Zealand so much and have been very well here."

From 1896 to 1897, she continued her duties as Assistant Mother General in Australia. In 1899 she was once again elected in a unanimous vote by her sisters to Mother General of the Institute of St. Joseph. Between the years 1899 to 1902, she traveled to South Australia several times and made two more trips to New Zealand to supervise the houses there.

Mary saw the work of the Institute not as a service to the public, but as an important effort and the spirit of Christianity lived through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. This in no way diminishes its value, but makes it all the more necessary and beautiful in the eyes of God. The dignity of the human person is something that needs to be protected and this has been the message of the Church throughout the centuries.

Mary’s whole life was one of charity to her neighbour and she practiced this to a very high degree. One sister says of her: "She had driven some miles in a snow storm, but her first wish was to visit the school. There was a poor little bare-footed and ragged boy standing in class. Mother went straight to him, and putting her arms around him she kissed him saying, ‘Ah, Sister, these are the children I love.’"

In 1902, Mary returned once again to New Zealand not to establish another convent or Refuge, but because of her severe rheumatism. She suffered a stroke and became incapable of walking on her own except for very short distances. Many people with whom she had been in contact with during her busy life came to visit her and were again edified by this remarkable woman.

"My first impression was that I met an extraordinary person," was a common statement by her visitors. During her last sufferings, she still found the strength to share her wisdom with her sisters. "My own dear Sisters, let us refuse nothing to God’s love. He humbled Himself and suffered for us – let us be glad to show Him we are willing to suffer whatever He deigns to ask of us."

One of the sisters, who assisted her during her last moments, recounted what took place during Mary’s last few hours on earth. "There was no struggle at her death. She was conscious up to the moment of her death, and was able to press my hand. The blessed candle was in her hand all the time."

Mother Mary Mackillop died on August 8, 1909. Her last words to her sisters were, "Whatever troubles may be before you, accept them cheerfully, remembering Whom you are trying to follow. Do not be afraid. Love one another, bear with one another, and let charity guide you in all your life."

Mary Mackillop was beatified January 19, 1995 by Pope John Paul II.

During the ceremony he spoke of Mary’s mission in Australia and New Zealand and the promotion of the Josephites around the world.

"We are gathered here in Sydney to venerate and invoke the intercession of this fervent and stalwart woman whom the Lord made ‘holy and blameless and irreproachable before him’ (Col. 1:22).

"The beatification of Mary MacKillop reminds us that all efforts to renew the face of the earth (cf. Ps. 104:30) are sterile if they are not grounded in the gift of new and abundant life by which a person ‘is brought into the supernatural reality of the divine life itself and becomes a ‘dwelling place of the Holy Spirit,’ ‘a living temple of God’ (Dominum et Vivificantem, 58).

"Dear friends: Mary MacKillop cannot be understood without reference to her religious vocation. The recent Synod of Bishops on the consecrated life reflected on many questions regarding consecration itself. What clearly emerged from the synod’s discussion is the fact that the consecrated life is a specific vocation, not to be confused with other forms of commitment and dedication to the apostolate. People look to religious to walk side by side with them along the path of life, precisely as those who are wise in the ways of God. Mother Mary of the Cross did not just free people from ignorance through schooling or alleviate their suffering through compassionate care. She worked to satisfy their deeper, though sometimes unconscious longing for ‘the unsearchable riches of Christ’ (Eph. 3:8).

"Today we praise you, O God, for your gracious gift to us of Mother Mary of the Cross. We thank you for the wonders of holiness which you wrought in her as a disciple of Jesus and a faithful daughter of the church. Beloved sisters and dear friends: From this day forward you will have a powerful intercessor before the throne of God in the person of Blessed Mary MacKillop. I pray that her example of ardent love for the church, the body of Christ, will ever inspire you to serve the Lord with gladness – in the weak, the brokenhearted and the oppressed. In Mary MacKillop all Australians have a sign of the flowering of holiness in their midst Let us truly ‘rejoice and be glad’ (Ps. 118:24). Amen."

Quotes are taken from: "An Extraordinary Australian: Mary MacKillop" by Paul Gardiner S.J.