Banks create money as a debt

Economic Democracy - Lesson 3

Money begins in the banks

In the previous lesson, we gave the following example: Let us suppose I am a businessman. I want to set up a new factory. All I need is money. I go to a bank and borrow $100,000 under security. The banker makes me sign a promise note to pay back the amount with interest. Then he lends me the $100,000.

Is he going to hand me the $100,000 in paper money? I do not want it. First, it is too risky. Furthermore, I am a businessman who buys things at different and widely far-flung places through the medium of cheques. What I want is a bank account of $100,000 which will make it easier for me to carry on business.

The banker will therefore lend me an account of $100,000. He will credit my account with $100,000, just as if I had brought that amount to the bank. But I did not bring it; I came to get it.

Is it a savings account, set up by me? No, it is a borrowing account made by the banker himself, for me.

Fractional-reserve banking

In this example, when I am granted a $100,000 loan, the banker actually created $100,000 of new money in the form of credit, in the form of bookkeeping money, which is just as good as coins and paper money.

The banker is not afraid to do this. My cheques to payees will give them the right to draw money from the bank. But the banker knows very well that nine-tenths of these cheques will simply have the effect of decreasing the money in my account, and of increasing it in other people's accounts. He knows very well that a ratio of bank reserves to deposits of 1/10 is enough for him to meet the requests of those who want pocket money. In other words, the banker knows very well that if he has $10,000 in cash reserves, he can lend $100,000 (ten times the sum) in bookkeeping money.

In technical terms, the capacity for a bank to lend 10 times the amount of paper money it has in its safe is called fractional-reserve banking. The origin of this system goes back to the Middle Ages. It is the true story of the goldsmiths who became bankers, as told now by Louis Even:

The goldsmith who became a banker

If you have some imagination, go back a few centuries to a Europe already old, but not yet progressive. In those days, money was not used much in everyday business transactions. Most of those transactions were simple direct exchanges, barter. However, the kings, the lords, the wealthy, and the big merchants owned gold, and used it to finance their armies'expenses, or to purchase foreign products.

If you have some imagination, go back a few centuries to a Europe already old, but not yet progressive. In those days, money was not used much in everyday business transactions. Most of those transactions were simple direct exchanges, barter. However, the kings, the lords, the wealthy, and the big merchants owned gold, and used it to finance their armies'expenses, or to purchase foreign products.

However, the wars between lords or nations, and armed robberies, were causing the gold and the diamonds of the wealthy to fall into the hands of pillagers. So the owners of gold, who had become very nervous, made it a habit to entrust their treasures for safekeeping to the goldsmiths who, because of the precious metal they worked with, had very well protected vaults. The goldsmith received the gold, gave a receipt to the depositor, and took care of the gold, charging a fee for this service. Of course, the owner claimed his gold, all or in part, whenever he felt like it.

The merchant leaving for Paris or Marseille, or travelling from Troyes, France, to Amsterdam, could provide himself with gold to make his purchases. But here again, there was danger of being attacked along the road; he then convinced his seller in Marseille or Amsterdam to accept, rather than metal, a signed receipt attesting his claim to part of the treasure on deposit at the goldsmith's in Paris or Troyes. The goldsmith's receipt bore witness to the reality of the funds.

It also happened that the supplier, in Amsterdam or elsewhere, managed to get his own goldsmith in London or Geneva to accept, in return for transportation services, the signed receipt that he had received from his French buyer. In short, little by little, the merchants began to exchange among themselves these receipts rather than the gold itself, in order not to move the gold unnecessarily and risk attack from robbers. In other words, a buyer, rather than getting a gold plate from the goldsmith to pay off his creditor, gave to the latter the goldsmith's receipt, giving him a claim to the gold kept in the vault.

Instead of the gold, it was the goldsmith's receipts which were changing hands. For as long as there was only a limited number of sellers and buyers, it was not a bad system. It was easy to follow the journey of the receipts.

The gold lender

The goldsmith soon made a discovery, which was to affect mankind far more than the memorable journey of Christopher Columbus himself. He learned, through experience, that nearly all of the gold that was left with him for safekeeping remained untouched in his vault. Barely more than one-in-ten of the owners of this gold ever took it out of the vault to conduct their business transactions, using their receipts instead for the purpose.

The thirst for gain, the longing to become rich faster than by means of the jeweller's tools, sharpened the mind of our man, and he made a daring gesture. "Why," he said to himself, "would I not become a gold lender!" A lender, mind you, of gold which did not belong to him. And since he did not possess a righteous soul like that of Saint Eligius (or St. Eloi, the master of the mint of French kings Clotaire II and Dagobert I, in the seventh century), he hatched and nurtured the idea. He refined the idea even more: "To lend gold which does not belong to me, at interest, needless to say! Better still, my dear master (was he talking to Satan?), instead of the gold, I will lend a receipt, and demand payment of interest in gold; that gold will be mine, and my clients'gold will remain in my vaults to back up new loans."

He kept the secret of his discovery to himself, not even talking about it to his wife, who wondered why he often rubbed his hands in great glee. The opportunity to put his plans into operation did not take long in coming, even though he did not have "The Globe and Mail" or "The Toronto Star" in which to advertize.

One morning, a friend of the goldsmith actually came to see him and asked for a favour. This man was not without goods — a home, or a farm with arable land — but he needed gold to settle a transaction. If he could only borrow some, he would pay it back with an added surplus; if he did not, the goldsmith would seize his property, which far exceeded the value of the loan.

The goldsmith got him to fill out a form, and then explained to his friend, with a disinterested attitude, that it would be dangerous for him to leave with a lot of money in his pockets: "I will give you a receipt; it is just as if I were lending you the gold that I keep in reserve in my vault. You will then give this receipt to your creditor, and if he brings the receipt to me, I will in turn give him gold. You will owe me so much interest."

The creditor generally never showed up. He rather exchanged the receipt with someone else for something that he required. In the meantime, the reputation of the gold lender began to spread. People came to him. Thanks to other similar loans by the goldsmith, soon there were many times more receipts in circulation than real gold in the vaults.

The goldsmith himself had really created a monetary circulation, at a great profit to himself. He quickly lost the original nervousness he had when he had worried about a simultaneous demand for gold from a great number of people holding receipts. He could, to a certain extent, continue with his game in all safety. What a windfall; to lend what he did not have and get interest from it, thanks to the confidence that people had in him — a confidence that he took great care to cultivate! He risked nothing, as long as he had, to back up his loans, a reserve that his experience told him was enough. If, on the other hand, a borrower did not meet his obligations and did not pay back the loan when due, the goldsmith acquired the property given as collateral. His conscience quickly became dulled, and his initial scruples nolonger bothered him.

The creation of credit

Moreover, the goldsmith thought it wise to change the way his receipts were set out when he made loans; instead of writing, "Receipt of John Smith..." he wrote, "I promise to pay to the bearer...". This promise circulated just like gold money. Unbelievable, you will say? Come on now, look at your dollar bills of today. Read what is written on them. Are they so different, and do they not circulate as money?

A fertile fig tree — the private banking system, the creator and master of money — had therefore grown out of the goldsmith's vaults. His loans, without moving gold, had become the banker's creations of credit. The form of the primitive receipts had changed, becoming that of simple promises to pay on demand. The credits paid by the banker were called deposits, which caused the general public to believe that the banker loaned only the amounts coming from the depositors. These credits entered into circulation by means of cheques issued on these credits. They displaced, in volume and in importance, the legal money of the Government which only had a secondary role to play. The banker created ten times as much paper money as did the State.

The goldsmith, transformed into a banker, made another discovery: he realized that putting plenty of receipts (credits) into circulation would accelerate business, industry, construction; whereas restriction of credits, which he practised at first in circumstances in which he worried about a run on the bank for gold, paralyzed business development. There seemed to be, in the latter case, an overproduction, when privations were actually great; it is because the products were not selling, due to a lack of purchasing power. Prices went down, bankruptcies increased, the banker's debtors could not meet their obligations, and the lenders were seizing the properties given as collateral.

The banker, very clear-sighted and very skillful when it came to gain, saw his opportunities, his marvellous opportunities. He could monetize the wealth of others for his own profit: by doing it liberally, causing a rise in prices, or parsimoniously, causing a decrease in prices. He could then manipulate the wealth of others as he wished, exploiting the buyer in times of inflation, and exploiting the seller in times of recession.

The banker, the universal master

The banker thus became the universal master, keeping the world at his mercy. Periods of prosperity and of depression followed one another. Humanity bowed down before what it thought were natural and inevitable cycles.

Meanwhile, scholars and technicians tried desperately to triumph over the forces of nature, and to develop the means of production. The printing press was invented, education became widespread, cities and better housing developed. The sources of food, clothing, and comforts increased and were improved. Man overcame the forces of nature, and harnessed steam and electricity. Transformation and developments occurred everywhere — except in the monetary system.

And the banker surrounded himself with mystery, keeping alive the confidence that the captive world had in him, even being so audacious as to advertize in the media, of which he controlled the finances; that the bankers had taken the world out of barbarism, that they had opened and civilized the continents. The scholars and wage-earners were considered but secondary in the march of progress. For the masses, there was misery and contempt; for the exploiting financiers, wealth and honours!

|

Source: http://www.currencymuseum.ca |

The ratio of cash versus loans in Canadian banks was about one for ten in the 1940s. This ratio (a 10% cash reserve requirement) has changed since then. In 1967, the Canadian Bank Act allowed the chartered banks to create sixteen times (in bookkeeping money) the sum of their cash reserves. Beginning in 1980, the minimum reserve required in cash (bank notes and coins) was 5 per cent, which meant that the banker needed only one dollar out of twenty to answer the needs of those who wanted pocket money. The banker knew very well that if he had $10,000 in cash, he could lend twenty times the sum, or $200,000, in bookkeeping money.

In practice, the banks could lend out even more than that, since they could increase their cash reserves at will by simply purchasing bank notes from the central bank (the Bank of Canada) with the bookkeeping money they create out of thin air, with a pen. For example, it was established in 1982, before a parliamentary committee on bank profits, that in 1981, the Canadian chartered banks, as a whole, made loans 32 times in excess of their combined capital. A few banks even lent sums equal to 40 times their capital. Moreover, in 1990 in the U.S.A., the total deposits of commercial banks amounted to about $3,000 billion, and their reserves amounted to approximately $60 billion. This resulted in a ratio of deposits to bank reserves of about 50/1. U.S. banks held enough cash to pay off depositors at the rate of only about two cents on the dollar.

Subsection 457(1) of the most recent version of the Canadian Bank Act, enacted on December 13, 1991, states that, as of January, 1994, the primary reserve, in the form of cash, that a chartered bank has to maintain is nil, zero. So the banks are no longer limited by law in creating credit, or bookkeeping money. (And, if all cash is eventually replaced by electronic money, with debit or microchip cards, as is already planned by the banks, they won't even be limited in practice to creating money, which will then not be a piece of paper or an entry in a ledger, but simply bytes, units of information in a computer.)

Money destroyers

So we have just seen that banks create money when they make a loan, as it was explained at the end of the previous lesson. The banker manufactures money, ledger money, when he lends accounts to borrowers, individuals, or governments. When I leave the bank, there will exist in this country a new source of cheques, one that did not exist before. The total amount of all accounts in the country was increased by $100,000. With this new money, I will pay the workers, buy materials and machinery — in short, build my new factory. Who, then, creates money? — The bankers!

The bankers, and the bankers alone, make this kind of money: bank money, the money that keeps business moving. But they do not give away the money they create. They lend it. They lend it for a certain period of time, after which it must be returned to them. The bankers must be repaid.

The bankers claim interest on this money that they have created. In the case mentioned in the previous lesson, with a $100,000 loan, the banker will probably demand $10,000 from me in interest, at once. He will withhold it from the loan, and I will leave the bank with $90,000 in my account, having signed a promise to repay $100,000 in one year's time.

In building my factory, I will pay my men, buy things, and thus spread my bank account of $90,000 throughout the country. But within a year, I must, through the profits I make selling my goods for more than they cost me, build my account up to not less than $100,000.

At the end of the year, I will pay back the loan by making out a cheque for $100,000 on my account. The banker will then debit my account by $100,000, therefore taking from me this $100,000 I have drawn from the country by selling my goods. He will not put this money into the account of anyone. No one will be able to draw cheques on this $100,000. It is dead money.

Borrowing gives birth to money. Repayment brings about its extinction. The bankers bring money into existence when they make a loan. The bankers send money to the grave when they are repaid. The bankers are therefore also destroyers of money.

Reginald McKenna Reginald McKenna |

As a distinguished British banker, the Right Honourable Reginald McKenna, one-time British Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Chairman of the Midland Bank, one of the Big Five (five largest banks of England), said: "Every loan, overdraft, or bank purchase creates a deposit, and every repayment of a loan, overdraft, or bank sale destroys a deposit."

And the system so operates that the repayment must be greater than the original loan; the death figures must exceed the birth figures; the destruction must exceed the creation.

This seems impossible, and collectively, it is impossible. If I succeed, someone else must go bankrupt, because, all together, we are not able to repay more money than has been made. The bankers create nothing but the capital sum. No one creates what is necessary to make up the interest, because no one else creates money. And yet, the bankers demand both capital and interest. Such a system cannot hold out except for a continuous and ever-increasing flow of loans. Hence the system of debts, and the strengthening of the dominating power of the banks.

The national debt

The Government does not create money. When the Government can no longer tax nor borrow from individuals, due to the scarcity of money, it borrows from the banks.

The operation takes place exactly like mine. As a guarantee, it pledges the whole country. The promise to pay back is the debenture. The loan of the money is an account made by a pen and some ink.

Thus, in October, 1939, the Federal Government, in order to cover the initial expenses of the war, asked some $80,000,000 from the banks. The banks lent the Government an account of $80 million without taking a cent from anyone, thus giving the Government a new base for cheques of $80 million. But, in October, 1941, the Government had to repay $83,200,000 to the banks, including both capital and the interest.

Through taxes, the Government had to remove from the country as much money as it had spent, $80 million, but, in addition, it had to draw from the country a further $3 million, money it had not put into the country, which had neither been made by the bankers nor by anyone else.

Even conceding at the most that the Government can find the money that exists, how can it find the money that has never been created? The plain fact is, the Government does not find it. It is simply added to the national debt. This explains why the national debt increases in the same measure as the country's development requires more money. All new money comes into existence as a debt, through the banker, who claims more money than he has actually issued.

And the country's population finds itself collectively indebted for a production that, collectively, it made itself! It is the case for war production. It is the case also for peacetime production: roads, bridges, waterworks, schools, churches, etc.

The monetary defect

The situation comes down to this inconceivable thing: all the money in circulation comes only from the banks. Even metal and paper money comes into circulation only if it has been released by the banks.

Now the banks put money into circulation only by lending it out at interest. This means that all the money in circulation comes from the banks, and must someday be returned to the banks, increased with the interest.

The banks remain the owners of the money. We are only the borrowers. If some manage to hang on to their money for a long period of time, or even permanently, others are necessarily incapable of fulfilling their financial commitments.

A multiplicity of bankruptcies, both for individuals and companies, mortgage upon mortgage, and an ever-increasing public debt, are the natural fruits of such a system.

Claiming an interest on money as it comes into existence is both illegitimate and absurd, antisocial and contrary to good arithmetic. The monetary defect is therefore as much a technical defect as a social defect.

As the country is developed, in production as well as in population, more money is needed. But it is impossible to get new money without contracting a debt which, collectively, cannot be paid.

So we are left with the alternatives of either stopping developments or of getting into debt; of either plunging into mass unemployment or into an unrepayable debt. And it is precisely this dilemma that is being debated in every country.

Aristotle, and after him, Saint Thomas Aquinas, wrote that money does not breed more money, but the banker brings money into existence only on the condition that it breeds more money. Since neither governments nor individuals create money, no one creates the interest claimed by the banker. Even if legalized, this form of issue remains vicious and insulting.

Decline and degradation

This way of making the country's money, by forcing governments and individuals into debt, establishes a real dictatorship over governments and individuals alike.

The sovereign Government has become a signatory of debts to a small group of profiteers. A minister, who represents millions of men, women and children, signs unpayable debts. The bankers, who represent a clique interested only in profit and power, manufacture the country's money.

Without blood, humans cannot survive; so it is fair to compare money with the economic lifeblood of the nation. Pope Pius XI wrote in 1931, in his encyclical letter Quadragesimo Anno:

"This power becomes particularly irresistible when exercised by those who, because they hold and control money, are able also to govern credit and determine its allotment, for that reason supplying, so to speak, the lifeblood to the entire economic body, and grasping, as it were, in their hands the very soul of production, so that no one dare breathe against their will."

"This power becomes particularly irresistible when exercised by those who, because they hold and control money, are able also to govern credit and determine its allotment, for that reason supplying, so to speak, the lifeblood to the entire economic body, and grasping, as it were, in their hands the very soul of production, so that no one dare breathe against their will."

A few lines further, the Pope spoke of the degeneration of power that ensues, saying that governments have surrendered their noble functions, and have become the servants of private interests.

The Government, instead of guiding the State, has become a mere tax collector, and a great slice from tax revenues, the most sacred slice, kept above all discussion, is purely and solely for the interest on the national debt.

Furthermore, the legislation consists, above all, in taxing people and setting up, everywhere, restrictions on freedom.

There are laws to ensure that the money creators are repaid. There are no laws to prevent a human being from dying of extreme poverty.

As for individuals, the scarcity of money develops a mentality of wolves. In the face of plenty, only those who have money — the too scarce symbol of goods — are given the right to draw on that plenty. Hence the counterproductive competition, the tyranny of the "boss", domestic strife, etc.

A small number preys on all the others. The great mass of the people groan, many in the most degrading poverty.

The sick remain without care; children are poorly or insufficiently nourished; talents go undeveloped; youths can neither find a job nor start a home or family; farmers lose their farms; industrialists go bankrupt; families struggle along with difficulty — all this without any other justification than the lack of money. The banker's pen imposes privations on the people, servitude on the governments.

With all this said, a striking point must be emphasized: it is production that gives value to money. A pile of money without corresponding products does not keep anyone alive, and is absolutely worthless. Thus, it is the farmers, the industrialists, the workers, the professionals, the organized citizenry, who make products, goods and services. But it is the bankers who create the money, based on these products. And the bankers appropriate this money, which draws its value from the products, and lend it to those who make the products.

A debt-money system: The Money Myth Exploded

The way money is created by private banks as a debt is well explained in Louis Even's parable, The Money Myth Exploded, in which the economic system is clearly divided into two parts: the producing system and the financial system. So, on the one side, there are five shipwrecked people on an island, who produce all the necessities of life, and on the other side, a banker, who lends them money. To simplify this example, let us say there is only one borrower on behalf of the community; we'll call him Paul.

The way money is created by private banks as a debt is well explained in Louis Even's parable, The Money Myth Exploded, in which the economic system is clearly divided into two parts: the producing system and the financial system. So, on the one side, there are five shipwrecked people on an island, who produce all the necessities of life, and on the other side, a banker, who lends them money. To simplify this example, let us say there is only one borrower on behalf of the community; we'll call him Paul.

Paul decides, on behalf of the community, to borrow a certain amount of money from the banker, an amount sufficient for business in the little community, say $100, at 6% interest. At the end of the year, Paul must pay the bank an interest of 6%, that is to say, $6. 100 minus 6 = 94, so there is $94 left in circulation on the island. But the $100 debt remains. The $100 loan is therefore renewed for another year, and another $6 of interest is due at the end of the second year. 94 minus 6, leaves $88 in circulation. If Paul continues to pay $6 in interest each year, by the seventeenth year there will be no more money left in circulation on the island. But the debt will still be $100, and the banker will be authorized to seize all the properties of the island's inhabitants.

Production has increased on the island, but not the money supply. It is not products that the banker wants, but money. The island's inhabitants were making products, but not money. Only the banker has the right to create money. So, it seems that Paul wasn't wise to pay the interest yearly.

Let's go back to the beginning of our example. Let's say that at the end of the first year, Paul chooses not to pay the interest, but to borrow it from the banker, thereby increasing the loan principal to $106. "No problem," says the banker, "the interest on the additional $6 is only 36 cents; it is peanuts in comparison with the $106 loan!" So the debt at the end of the second year is: $106 plus the interest at 6% of $106, $6.36, for a total debt of $112.36 after two years. At the end of the fifth year, the debt is $133.82, and the interest is $7.57. "It is not so bad," thinks Paul, "the interest has only increased by $1.57 in five years. We can handle that." But what will the situation be like after 50 years?

$100 debt growth at 6% interest |

||||

| Year | Original borrowed capital | Debt at year end* | Interest due at year end | Money in circulation |

| 1 | $100 | $106.00 | $6.00 | $100 |

| 2 | $100 | $112.35 | $6.36 | $100 |

| 3 | " | $119.10 | $6.74 | " |

| 4 | " | $126.25 | $7.15 | " |

| 5 | " | $133.82 | $7.57 | " |

| 10 | " | $179.08 | $10.14 | " |

| 20 | " | $320.71 | $18.15 | " |

| 30 | " | $574.35 | $32.51 | " |

| 40 | " | $1,028.57 | $58.22 | " |

| 50 | " | $1,842.02 | $104.26 | " |

| 60 | $100 | $3,298.77 | $186.72 | $100 |

| 70 | $100 | $5,907.59 | $334.39 | $100 |

| * includes interest due | ||||

The debt increase is moderate in the early years, but the debt increases very fast with time to unbelievably big numbers. And note, the debt increases each year, but the original borrowed principal (amount of money in circulation) always remains the same. At no time can the debt be paid off with the money that exists in circulation, not even at the end of the first year: there is only $100 in circulation, and a debt of $106 remains. And at the end of the fiftieth year, all the money in circulation ($100) won't even pay the interest due on the debt: $104.26.

All money in circulation is a loan and must be returned to the bank, increased with interest. The banker creates money and lends it, but he has the borrower's pledge to bring all this money back, plus other money he did not create. Only the banker can create money: he creates the principal, but not the interest. And he demands that we pay him back, in addition to the principal that he created, the interest that he did not create, and that nobody else created either. As it is impossible to pay back money that does not exist, debts accrue.

The public debt is made up of money that does not exist, that has never been created, but that governments nevertheless have committed themselves to paying back. An impossible contract, represented by the bankers as a "sacrosanct contract", to be abided by, even though human beings die because of it.

Compound interest

The sudden increase in the debt after a certain number of years can be explained by the effect of what is called compound interest. Contrary to simple interest, which is paid only on the original borrowed capital, compound interest is paid on both the principal plus the accumulated unpaid interest. Thus, with simple interest, a $100 loan at 6% interest would give, at the end of 5 years, a debt of $100 plus 5 times 6% of $100 ($30.00), for a total debt of $130. But with compound interest, the debt at the end of the fifth year is the sum of the debt of the previous year ($126.35) plus 6% interest of this amount, for a total debt of $133.82.

Put all these results on a chart: the horizontal line across the bottom of the chart is marked off in years, and the vertical line is marked off in dollars. By connecting all these points by a line, we trace a curve, and you see the effect of compound interest and the growth of the debt:

The curve is quite flat at the beginning, but then becomes steeper as time goes on. The debts of all countries follow the same pattern, and are increasing in the same way. Let us study, for example, Canada's public debt.

Debt growth

To maintain $100 in circulation at 6% interest rateCanada's public debt

Each year, the Canadian Government draws up a budget wherein are estimated the expenditures and the revenues for the year. If the Government takes in more money than it spends, there is a surplus; if it spends more than it takes in, there is a deficit. Thus, for the fiscal year 1985/86 (the Government's fiscal year runs from April 1 to March 31), the Federal Government had expenditures of $105 billion and revenues of $71.2 billion, leaving a deficit of $33.8 billion. This deficit represents a deficiency in revenues. (The Federal Debt has managed to balance its budget over the recent years, but it is simply because it downloaded its deficit on provinces and municipalities, forcing them to make cuts in health and other basic services. This does not prevent the overall debt of all public administrations from continuing to increase.) The national debt is the total accumulation of all budgetary deficits since Canada came into existence (the Confederation of 1867). Thus, the 1986 deficit of $33.8 billion is added to the debt of 1985, $190.3 billion, for a total debt of $224.1 billion in 1986. (By January, 1994, Canada's public debt reached the $500-billion mark.)

When Canada was founded in 1867 (the union of four provinces — Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia), the country's debt was $93 million. The first major increase took place during World War I (1914-18), when Canada's public debt went up from $483 million in 1913 to $3 billion in 1920. The second major increase took place during World War II (1939-45), when the debt went up from $4 billion in 1942 to $13 billion in 1947. These two increases may be explained by the fact that the Government had to borrow large sums of money in order to take part in these two wars.

When Canada was founded in 1867 (the union of four provinces — Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia), the country's debt was $93 million. The first major increase took place during World War I (1914-18), when Canada's public debt went up from $483 million in 1913 to $3 billion in 1920. The second major increase took place during World War II (1939-45), when the debt went up from $4 billion in 1942 to $13 billion in 1947. These two increases may be explained by the fact that the Government had to borrow large sums of money in order to take part in these two wars.

But how can be explained the phenomenal increase of these last years, when the debt almost increased ten times, passing from $24 billion in 1975 to $224 billion in 1986, in peacetime, when Canada had no need to borrow for war?

It is the effect of compound interest, like in the example of the island in The Money Myth Exploded. The debt increases slowly in the early years, but grows extremely fast in the following years. And Canada's public debt has even increased more rapidly during these more recent years than during the example given in Louis Even's parable: on the island, the interest rate always remained at 6%, while this rate varied in Canada, rising from 2% during World War II to a high of 22% in 1981.

Here is another explanation for Canada's faster debt growth: unlike in Louis Even's parable, in which the money supply always remains the same, $100, the amount of money in circulation in Canada has increased many times since Confederation, which meant more borrowings... and more debts!

There is a big difference between interest rates of 6%, 10%, or 20%, when you speak of compound interest. The following are the sums that $1.00 will amount to in 100 years, loaned at the rates of interest shown and compounded annually:

at 1%................................... $2.75

at 2%................................. $19.25

at 3%............................... $340.00

at 10%.......................... $13809.00

at 12%...................... $1,174,405.00

at 18%..................... $15,145,207.00

at 24%................... $251,799,494.00

And at 50%, it would eat up the world! There is a formula to calculate approximately the amount of time it will take for an amount, at compound interest, to double; it is the "Rule of 72": You divide 72 by the interest rate. It gives you the number of years it will take for the amount to double. Thus, an interest rate of 10% will cause a loan to double in 7.2 years (72 divided by 10).

All this is to show that any interest demanded on money created out of nothing, even at a rate of 1%, is usury. In his November 1993 report, Canada's Auditor General calculated that of the $423 billion in net debt accumulated from Confederation to 1992, only $37 billion went to make up the shortfall in program spending. The remaining $386 billion covered what it has cost to borrow that $37 billion. In other words, 91% of the debt consisted of interest charges, the Government having spent only $37 billion (8.75% of the debt) for actual goods and services.)

| Canadian Debt 1867 - 1992 — $423 billion | ||

| $386 billion, or 91.25% of the debt, is made up of compound interest. (10.43 times the useful expenditures) |  |

Real spending on goods and services: $37 billion or 8.75% |

The effect of compound interestIn his November 1993 report, Canada's Auditor General calculated that of the $423 billion in net debvt accumulated from Confederation to 1992, only $37 billion went to make up the shortfall in program spending. The remaining $386 billion covered what it has cost to borrow that $37 billion. In other words, 91% of the debt consisted of interest charges, the Government having spent only $37 billion (8.75% of the debt) for actual goods and services. |

||

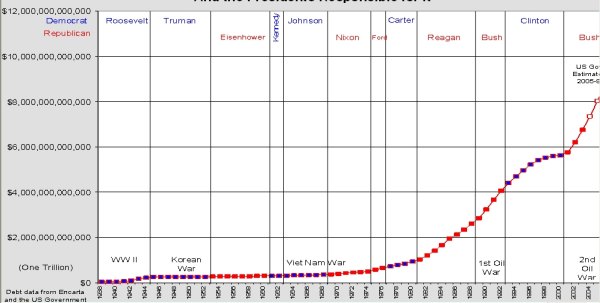

The public debt of the United States

The public debt of the United States follows the same curve as Canada's, but with figures ten times bigger. As was the case with Canada, the first significant increases in the public debt took place during war times: the American Civil War (1861-1865), World Wars I and II. For example, the debt, which totalled $1.2 billion in 1916, jumped to $25 billion in 1919. From 1939 to 1945, it went up from $40 billion to $258 billion. From 1975 to 1986, the debt went up from $533 billion to $2,125 billion.

United States National Debt (1938-2005)

In October 2005, the federal debt reached the $8 trillion mark ($26,672 for each U.S. citizen), and it is continuing to grow wildly out of control. (For the fiscal year 2004, the interest payments on the U.S. federal debt were $321 billion.) And that's only the peak of the iceberg: If there are public debts, there are also private debts! The Federal Government is the biggest single borrower, but not the only borrower in the country: there are also individuals and companies. In the United States, in 1992, the public debt was $4 trillion, and the total debt was $16 trillion, with an existing money supply of only $950 billion. In 2006, the total debt (states, corporations, consumers) is over $41 trillion!

In October 2005, the federal debt reached the $8 trillion mark ($26,672 for each U.S. citizen), and it is continuing to grow wildly out of control. (For the fiscal year 2004, the interest payments on the U.S. federal debt were $321 billion.) And that's only the peak of the iceberg: If there are public debts, there are also private debts! The Federal Government is the biggest single borrower, but not the only borrower in the country: there are also individuals and companies. In the United States, in 1992, the public debt was $4 trillion, and the total debt was $16 trillion, with an existing money supply of only $950 billion. In 2006, the total debt (states, corporations, consumers) is over $41 trillion!

| Previous chapter - Poverty amidst plenty - The birth and death of money | Next chapter - The solution: debt-free money issued by society |

The Swedish Stockholm bank note was used as currency in Sweden from the 1600's to the 1700's. In 1661, Swedish coins were huge. It would have been impossible to carry around 100 dalers in coins. The Swedish Stockholm Bank got permission from the government to produce bank notes. This way coins could stay in the bank and people could carry pieces of paper that represented the coins instead. These types of bank notes were the first printed paper money to be used in Europe.

The Swedish Stockholm bank note was used as currency in Sweden from the 1600's to the 1700's. In 1661, Swedish coins were huge. It would have been impossible to carry around 100 dalers in coins. The Swedish Stockholm Bank got permission from the government to produce bank notes. This way coins could stay in the bank and people could carry pieces of paper that represented the coins instead. These types of bank notes were the first printed paper money to be used in Europe.