Money, or Credit, is a Social Instrument

To Issue it, Should be the Role of Society

Louis Even Louis Even |

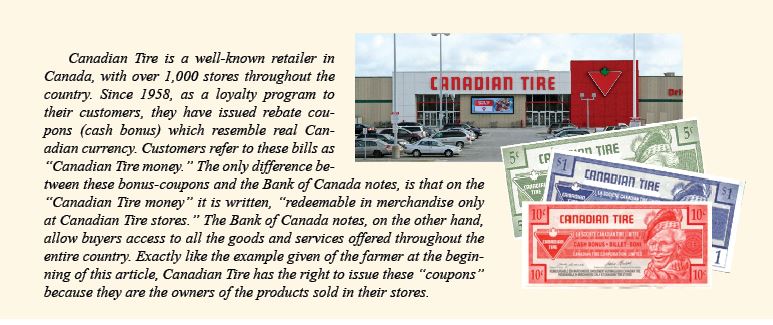

Let us just say that I am a farmer. I need a hired man to help me in my work. Lacking the money needed to pay him, I might possibly arrive at a settlement whereby I will pay him with something else besides money.

I can, for example, agree to give him ten pounds of potatoes, three pounds of meat, one pound of butter and one gallon of milk, for every day of work that he gives me. The products, of course, will come from my own farm.

I can also estimate the value of his work in dollars, without actually giving him any, since I don’t have them. In this case then, each day I can sign a ticket, for example, permitting him to choose from among the many products on my farm, those things which he wants to the value of five dollars for each hour of work he does. Here again, I give him the right to choose from among the products on my farm.

However, I certainly cannot sign tickets that give him the right to choose from among the products made by other farmers or by other craftsmen in town. I can only give him claim to those things which strictly belong to me.

But if I pay him in dollars — well, that is a different story. He can then choose goods or services from any source, anywhere in the country. But in order to pay him in money, I must first of all have the money.

The difference between a ticket issued by me, and money, is that my ticket only gives him a right to those things which belong to me. Whereas, money gives him a right to the products of others, as well as to my own products.

I can use tickets on my own products because I make these products; I am their owner. I cannot issue (create) money because I am not the owner of everyone else’s products.

Both the tickets and the money can be made of the same size paper. Both can bear the same numbers —my ticket can be labeled “ten dollars”, just as a ten-dollar note issued by the Bank of Canada is labeled “ten dollars.” But my ticket can only buy my products. Whereas the ten dollars of paper money can buy any goods or services, anywhere in the country, for the amount of this value.

A social instrument

All of this is just another way of saying that money is a social instrument. And since it gives a claim to everyone’s goods and services, it cannot justifiably be issued by an individual or by private corporations. It would amount to attributing to oneself the right to dispose of products made by other people.

And yet new money must begin somewhere, it must be created somewhere. The money that is already in circulation certainly did not fall from heaven like manna. It did not come into being by spontaneous generation. Similarly, when production increases, the volume of money in circulation must necessarily increase. Canada’s present-day industry and commerce would be paralyzed if there were not more money in the country than there was during the time of Champlain, in the 1600’s!

Therefore, the money supply did increase. There was new money added. And since the industrial activity has increased, then so must the money supply. But where will this additional money come from, since no private individual or group of private individuals has the power to issue claims on the property of others?

This new money — this increase in the money supply — can come from no other source than society itself, through the agency of an organism established to fulfill this function on behalf of society.

Who today fulfills this function, which is, from its very essence, a social function? It most certainly is not the government, since the government has no money to spend except for that which it obtains through taxes or loans, and which it eventually repays through tax increases.

Money is created by the banks

A small part of modern money is made up of coins and bank notes. But by far, the greatest portion is made up of credit existing in the ledgers of banks.

Everyone knows that if you have a bank account, you can pay for your grocery bill without taking cash out of your pocket. You only need to make a personal check for the required amount and the merchant, who accepts the check, has only to go to the bank and deposit it into his own account or, if he prefers, take bank notes or coins in exchange.

Everyone knows that. But what everyone does not know is that there are two types of accounts which one can have at the bank. The first, is a savings account: the depositor comes to the bank to deposit his own money into his account. The other is an account opened by a borrower, who asks the bank to deposit money into an account for him.

There is a huge difference between these two kinds of accounts. With a savings account, you take your own money to the bank. The banker then places this money in his vault and inscribes into your account that amount of money to your credit. You, in turn, may use this money/credit however you wish — drawing on this account by making checks which, though they are not notes and coins—like the money you carried into the bank—they are money just the same.

But what about the borrower’s account? The borrower does not bring any money to the bank. He goes there to ask for money from the bank. Usually a larger sum—let us say something like $50,000. The banker is not going to reach into his drawer and take out $50,000 in hard cash and give it to the borrower. Even the borrower would hesitate before leaving the bank with such a large sum of money in his possession. What the borrower wants is to have $50,000 inscribed to his credit in his account. He will then be able to make checks according to his needs. The banker will do this for the borrower; he will inscribe this amount to the borrower’s credit.

But notice one thing, the banker does this without removing one penny from his drawer! And the borrower did not even bring one penny to the bank, nor was anyone else’s bank account touched in any way!

In the case of the depositor, there was a transformation. The hard cash was locked up in the banker’s drawer and became financial credit, which appeared as figures in the savings account of the depositor, and this transaction did not put one additional penny into circulation.

In the case of the borrower, there was no such transformation. The borrower did not bring any money with him into the bank and since nothing was taken from either the vault, or the drawer, or from any of the accounts of any of the other depositors, it now happens that there is in the bank’s ledger, to the credit of the borrower, a new sum of money which did not exist before.

This is what is called the “creation of money” by the banker. It is a creation of credit, of bankbook money. This money is just as good as any other money, since the borrower can draw checks from it in the same way that the depositor can draw on the money that he deposited.

With this new money, the borrower can pay for work, materials, goods—the work of others, the materials of others, the goods of others.

In creating this $50,000 for the borrower, the banker has given him the right to draw upon the production of others. Not the production of the banker, but upon all the production in the country. The banker, who does not own one bit of the country’s production, has, nevertheless, permitted himself to give the borrower a claim to the share of the country’s production.

This is what might be called, in all justice, the illegitimate use of a social function. Only society as a whole can, in justice, accomplish this function; a function which society may very well entrust to a competent organism, under its own control. But it is inadmissible that so important a social function be delegated to a private institution who only traffics it for their own profit.

A sovereign power over economic life

The borrower, at an agreed upon time, must repay to the bank the money which has been created for him. When this money returns to the bank, it ceases to exist and is no longer in circulation; the money is canceled. In order to put more money into circulation, another loan would be required; another “creation” of bankbook money.

Loans therefore, put money into circulation and repayment of loans withdraw money from circulation.

In a given period — let us say, a year — if the sum of the bank loans granted, is greater than the sum of the repayments made, then the volume of money in circulation will have increased. If, on the contrary, the banks have been more difficult about granting loans, while still demanding repayment, at the same rate as previously, then the volume of money in circulation decreases. This is what is known as a restriction of credit.

Since the banker charges interest on his loans, every repayment entails the return of more money to the banker than was originally issued in the loan. The result is that, in order to keep up the volume of money in circulation, it is necessary to have, over all, a greater activity in loans than in repayments.

The fact that it is necessary to repay to the bank more money than was issued, results in private individuals and public bodies being obliged to have recourse continually to new loans, whence comes the ever-increasing debt. Without such a practice, it would not be long before the amount of money in circulation would dry up completely. This function of the banker therefore, confers upon him supreme power over the economic life of the country. He is more powerful than the government, for he has the power to grant, refuse and regulate credit, which is the very lifeblood of any country’s economy.

Statesmen in Europe, the United States and Canada have denounced, even openly, this supremacy of the banking system. Canada’s Prime Minister, Mackenzie King, said in 1935, that as long as this power remained unbroken, it was futile to speak of democracy and the sovereignty of Parliament. There have been those who, like him, promised to restore to the nation the control of its money and credit. Others, like former Canadian Finance Minister, Donald Fleming, have publicly attacked the arbitrary and harmful acts of the top bankers.

And yet none of these men were able to effect any change. And those politicians who are most vocal in their attacks on this money power will never change anything as long as the people themselves have not united to form a power even greater than that of the Financiers, a power that will force the government to take action.

This is not a matter to be settled by elections. It is a question of forming a large enough group of citizens who are enlightened and determined to the point where they will make themselves heard by their government, regardless of what party is in office.

It is also a matter for Divine assistance, since the enemy has a diabolical nature, and the money dictatorship is only one of his multiple faces. This is what the Social Creditors of the MICHAEL Journal have understood, and understand more and more.