by Dom Antoine Marie osb

One evening, a little girl saw, from her bedroom window, some women dressed in white, walking back and forth in a garden while chanting psalms. She asked her mother what they were doing. "They're nuns. They're praying." The little girl went on, "What is a nun? And who are they praying to?" — "They're praying to their God." — "Where is God? Why are they praying instead of going to bed?" The mother, agnostic, did not know how to answer. "How good it must be to be able to pray to God..." sighed the little girl, who added, under her breath, "My God, I also want to pray!" Hildegard had just taken her first step on a long path in search of Truth.

Hildegard Lea Freund was born on January 30, 1883 in Goerlitz, Saxony (on the present-day German-Polish border), into a family of non-practicing Jews. In 1895, the Freund family moved to Berlin, where Hildegard went to high school. She displayed great intellectual gifts and a deep desire for moral integrity; she wanted to become an "ethical person," which for her meant a woman of conviction and principles. She was not concerned about those things that typically excite teenagers — clothes, pastimes, being in the popular group... Rather, she was interested in philosophy, art, and culture. Nevertheless, her gaze did not extend beyond the present life. After reading Schopenhauer, for whom belief in a transcendent absolute and seeking eternal happiness were nothing but a vain illusion, she would write a poem with the disillusioned refrain, "Joys and sorrows pass. The world passes — there is nothing!"

Already before the birth of Jesus Christ, the Book of Wisdom put on the lips of unbelievers these words: We were born by mere chance, and hereafter we shall be as though we had never been (Wis. 2:2). After her conversion, Hildegard confided, about someone who had committed suicide: "So why should one struggle with this world, if one does not believe in the hereafter? I am sure that I too would kill myself if I did not believe. I do not understand how people can live without believing in God." Pope Benedict XVI likewise observed, in the encyclical Caritas in Veritate, "Without God man neither knows which way to go, nor even understands who he is" (no. 78).

In 1899, the Freund family moved to Zurich, Switzerland. After graduating high school in 1903, Hildegard entered the university, a rare privilege for young women in her day. She studied German literature and philosophy, under two Protestant professors, Saitschik and Foerster, who taught a system called the "philosophy of life," which, counter to the prevailing rationalism, affirmed that man was capable of knowing God. Saitschik insisted that purity of heart and uprightness of soul were necessary for such knowledge. Hildegard, moved but not convinced, repeated over and over, in tears and supplication, the "prayer of the unbeliever": "My God, if You exist, let me find You!" But for the moment she received no response.

In 1907, Hildegard returned to Berlin to study economics and social policy. There, she met Alexander Burjan, a Jewish Hungarian engineer who was agnostic and, like her, was seeking the deep meaning of life. They married within the year. In October 1908, an attack of renal colic forced the young woman to be hospitalized in the Saint Hedwig Catholic hospital in Berlin. Her health deteriorated to the point that she had to undergo several operations. During Holy Week of 1909, she was at the point of death, and the doctors had lost all hope of saving her. Against all expectations, on Easter Monday, her health markedly improved. After seven months of hospitalization, she was able to return home. However, she would suffer from the aftereffects of this kidney condition for the rest of her life.

During her long stay in the hospital, Hildegard had admired the devotion and charity of the Sisters of Mercy of Saint Borromeo (members of an Order founded by Saint Charles Borromeo, the archbishop of Milan, who died in 1584). She observed, "Only the Catholic Church can achieve this miracle of filling an entire community with such a spirit... Man, left to only his natural faculties, cannot do what these Sisters do. In seeing them, I experienced the power of grace." It was after this revelation of the "unshakable truth" of the Church through the holiness of her members that Hildegard converted. After a period of catechumenate, she received Baptism on August 11, 1909. This decisive act was the culmination of a long spiritual journey. After having long thought that man could, by dint of intelligence and will, achieve moral progress on his own, she now wrote, "It is not by human wisdom alone that we can do good, but only in union with Christ. In Him we can do all things; without Him, we are completely helpless."

"Man does not develop through his own powers," wrote Pope Benedict XVI in Caritas in Veritate... "In the course of history, it was often maintained that the creation of institutions was sufficient to guarantee the fulfillment of humanity's right to development. Unfortunately, too much confidence was placed in those institutions, as if they were able to deliver the desired objective automatically. In reality, institutions by themselves are not enough, because integral human development is primarily a vocation... Moreover, such development requires a transcendent vision of the person, it needs God: without Him, development is either denied, or entrusted exclusively to man, who falls into the trap of thinking he can bring about his own salvation, and ends up promoting a dehumanized form of development. Only through an encounter with God are we able to see in the other something more than just another creature, to recognize the divine image in the other, thus truly coming to discover him or her and to mature in a love that becomes concern and care for the other" (no. 11).

Baptism was for Hildegard the beginning of a new life. Radiant, she confided her happiness to her closest family and friends. In August 1910, she had the joy of seeing her husband Alexander baptized. Shortly thereafter, Hildegard was pregnant and preparing for a difficult delivery. The doctors advised her to abort her child because of the grave risk she was running. But she vigorously refused: "That would be murder! If I die, I will then be a victim of my 'profession' of mother, but the child must live!" The delivery went well, and little Lisa was born. She would be the only child in the Burjan family, whose life would from that point on unfold in Vienna, where Alexander became the head of a telephone equipment company.

Hildegard was certain that her life, saved by providence, must be entirely consecrated to God and mankind. Her vocation would be to proclaim to the poor God's love for them through social action. Before long, she discovered the terrible reality of workers'conditions. The poor, newly arrived in Austria's capital, lived crammed into unsanitary tenements. Men, women, and children worked in factories twelve to fifteen hours a day for starvation wages. In this environment, women were often tempted to prostitute themselves and abandon their children. To remedy the situation, the Church would create associations of Catholic women to fight not only to protect the morals of women factory workers, but also to defend their rights in the face of unscrupulous employers. Hildegard committed herself wholeheartedly to these efforts, armed with the deep understanding of social issues she had acquired at the university. In particular, she came to the defense of workers who worked at home and were paid at the employer's discretion, without any social security whatsoever.

In September 1912, Hildegard spoke at the annual gathering of Catholic women's leagues in Vienna: "Let us examine if we are not complicit in the misery of the people. We should buy only from conscientious shopkeepers, not pushing them to lower their prices, but demanding from time to time that the manufacturers account for the origin of their products. Too often, the well-off woman pressures storekeepers to sell at unrealistic prices, which is always at the expense of impoverished home workers." Almost alone at the outset in defending these workers "without a voice", she soon recruited volunteer collaborators from among the well-to-do.

That same year, Hildegard founded the "Association of Christian Women Home Workers," which offered its members better wages, social protection, legal assistance, and the possibility of an education. At the cost of great effort and frequent humiliations, she tried to win the support of those who were reluctant, even hostile. She thought that women had the right to a profession, including an intellectual one, to the extent that the work would not infringe upon their natural roles as wives and mothers. But this right must not be a pretext for exploiting their weakness. She also attended to the needs of children who were forced to earn a living — one-third of children in Vienna were in this situation. In violation of the law, children as young as six were working 14 hours a day, in factories or at home. These little slaves suffered an appalling mortality rate. Even those who survived into adulthood remained mentally impacted.

Distressed by this scandal, Hildegard denounced the exploitation of children in a pamphlet, drawing her inspiration from the teaching of Pope Leo XIII in the encyclical Rerum Novarum (1891). Charity towards the poor must not be limited to relieving isolated instances of suffering, without seeking to right the injustices that cause them. Each person must take responsibility, including in the political realm, to pull out the structures of sin at their roots, and establish social justice. During the First World War, Hildegard defended women who were replacing men in the factories who had been called up. Her goal: to apply the principle of "equal pay for equal work" on behalf of female workers. In November 1918, the defeat of the Central Powers (Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire) led to an insurrection in Vienna and the proclamation of the Austrian Republic. Nominated as a candidate in the parliamentary elections, Hildegard Burjan became the only woman representative of the Christian Socialist Party. In Parliament, she promoted social reforms, not as a revolutionary, but in fidelity to the social doctrine of the Church. She proposed laws to promote the rights of workers and to protect children. At her instigation, the parties agreed to pass a law offering social security to home help.

Hildegard said, "A consuming interest in public affairs is part of the practice of Christianity." Seventy years later, Blessed John Paul II would declare: "The lay faithful are never to relinquish their participation in'public life', that is, in the many different economic, social, legislative, administrative and cultural areas, which are intended to promote organically and institutionally the common good" (Post-synodal exhortation Christifideles Laici, December 30, 1988, no. 42).

During the two years of her term of office, Hildegard won the respect of all the members of Parliament. Chancellor Ignaz Seipel would say that he had never met anyone more enthusiastic in his or her political activity or wiser in his or her intuitions. Cardinal Piffl, the Archbishop of Vienna, saw in her "the conscience of the Parliament." Invited to run in the 1920 elections, and proposed for the post of Minister of Social Affairs, she declined both these offers, in part due to her poor health, but mostly to devote herself to organizing Caritas Socialis (Social Charity), an initiative whose goal and name were inspired by Saint Paul's exclamation (2 Cor. 5:14): Caritas Christi urget nos — For the love of Christ impels us.

Hildegard understood that, in order to achieve her goal and truly have an impact, those engaged in social action needed to be entirely motivated by the ideal presented in the Gospels. From this came her idea to found a community of women consecrated to God to promote social justice in the heart of working cities where Christianity had become foreign. Compelled by divine charity, these women would live according to the "Evangelical Counsels" (poverty, chastity, and obedience), wearing a simple and discrete religious habit, close to the workers. Hildegard formulated the foundational intuition of Caritas Socialis in these words: "Over the course of the centuries, the Catholic Church has nurtured the most varied flowers. In the face of each distress that has presented itself, she has sent forth men filled with the Holy Spirit to remedy it... Perhaps in its turn, our Caritas might, in the midst of modern paganism, appear as its own branch on the trunk of the Church." The plan was approved by Cardinal Piffl and blessed by Pope Benedict XV.

On October 4, 1919, the first ten Sisters of the Apostolic Society of the Sisters of Caritas Socialis made their commitment before God during a Mass in Vienna. Lay associates would work alongside them. The ambition of the Caritas was to dedicate itself to new charitable initiatives — providing a roof for homeless women, saving poor young women in danger, taking in single mothers to keep them from the temptation to abort their children (a "Home for mother and child" was opened in Vienna in 1924), rescuing prostitutes from vice by rehabilitating them, caring for women suffering from venereal diseases, etc. This apostolate scandalized some Catholics, who saw in it an encouragement of, or at least an excuse for, immorality. In reality, as Hildegard wrote, "It is not a question of only relieving material destitution, but in fact of awakening a new life in Christ." These so-called "lost" or endangered women were called to conversion and to lead a Christian life from then on. Caritas gave them the means to do so.

A married woman and the mother of a family, as foundress Hildegard Burjan acted as the superior of the Sisters, an anomaly that aroused criticism from some of the faithful. But Cardinal Piffl answered them: "Having Mrs. Burjan in my diocese is a grace for which I will be accountable before God. It is my holy conviction that she must remain the leader of the Sisters until her last breath." Overburdened, and overwhelmed with work, the foundress used to say, "I will rest and sleep only when I am under ground."

She dedicated a great deal of time to receiving and advising the Sisters. She showed them the respect due to women consecrated to God in the celibate life. Modesty, discretion in speech, but also charity and human warmth were the qualities she showed in this spiritual direction. To reprimand a Sister for a fault cost her dearly, but she spoke frankly when it was her duty. She did so in such a loving and constructive manner that Sisters left these meetings feeling won-over and at peace. Such a consuming job did not prevent Hildegard from remaining a very loving spouse and available mother. A bit before her death, she told her husband: "I have been very happy with you. Thank you for all these beautiful years that we have spent together, for your understanding and your assistance in my work."

Prayer was a fundamental necessity for Hildegard. Without God, nothing useful can be done (cf. John 15:5). She prayed especially at night, for lack of time during the day, taking time out of her sleep. A diabetic, Hildegard had to give herself insulin injections every day for fifteen years. She patiently endured all the sufferings of this disease — pain in her kidneys and intestines, exhaustion, hunger caused by the strict diet she was prescribed, and above all, a burning thirst. Every day, she attended Mass and received Communion. According to the discipline in effect at the time, to receive Communion, one needed to fast from all food and drink, including water, since midnight. Every morning, she waited for her husband to eat his breakfast and leave for the office; then she would go to Mass and only drink when she returned home. She never asked for a dispensation from the Eucharistic fast. Speaking from experience, Hildegard wrote one of her nuns: "Believe me, for everyone life is a battle. Aware of it or not, each of us advances slowly on the rocky road to Calvary. Let us thank God for giving us the opportunity to climb it and, by his light, to enable us to see our faults."

On Pentecost 1933, she suffered a very painful renal inflammation. In spite of the reassuring medical prognoses, Hildegard calmly prepared herself for a death she felt near. Her doctor gave the following account of her last days: "I have seen countless patients near death. But the final hours of Hildegard Burjan remain in my memory as a unique case. Fully aware of being close to her end, she was concerned about her loved ones and her initiatives. With respect to herself, she was without fear, and entirely surrendered; she joyfully considered death a deliverance from earthly existence, and showed an absolute confidence that she would enter into eternal life."

For her part, Hildegard confided, "My death is a calm Deo gratias! Twenty-five years ago, God, at the time of this illness, drew me to Himself and chose me. He carried me in His arms like a child, and now He is delivering me from this illness to lead me to Himself. I often think about what could be a cause for fear for me, of the moment of appearing before God... Certainly I have done many bad things in my life, but I know I have never sought anything but His will. And this is why I see nothing I should fear." She testified to her calm faith in these words: "Sometimes over the course of my life, the thought has come to me of what the hour of my death would be like, this moment at which all illusion ceases. I have wondered if then everything would dissolve, would appear to me as a dream... And now, I see that it is all true, that it is all Truth." On June 11, 1933, the Feast of the Most Holy Trinity, she murmured, "How beautiful it will be to go to rest in God!" Then, kissing her Crucifix, she said, in a slow and clear voice: "Dear Savior, make all men lovable, so that You might love them. Enrich them with Yourself alone!" Shortly thereafter, she died.

At the time of Hildegard's death, the Caritas Socialis numbered 150 members and 35 institutions in Austria and abroad. Raised in 1960 to a religious institute of pontifical right, today this "Community of Apostolic Life" comprises 900 sisters and lay collaborators who perform various apostolates, particularly on behalf of pregnant mothers in difficult circumstances (women's shelters), and for elderly persons suffering from serious medical conditions (Alzheimer's disease). Following a decree by Pope Benedict XVI, Hildegard Burjan was proclaimed blessed on January 29, 2012, in Vienna. In their commitment vows composed by Blessed Hildegard Burjan, the Caritas Sisters say to God: "I thank You with all my heart for having deemed me worthy to be an instrument of Your love."

Let us ask Jesus Christ, sent into the world by His Father to light the fire of Love (cf. Lk. 12:49), to make us instruments of His redemptive Love as well.

Dom Antoine Marie osb

This article is reprinted with permission from the Abbey of Clairval, France, which publishes every month a spiritual newsletter on the life of a saint, in English, French, Italian, or Dutch. Their postal address: Dom Antoine Marie, Abbe, Abbaye Saint-Joseph de Clairval 21150 Flavigny sur Ozerain, France. Their website: http:// www.clairval.com.

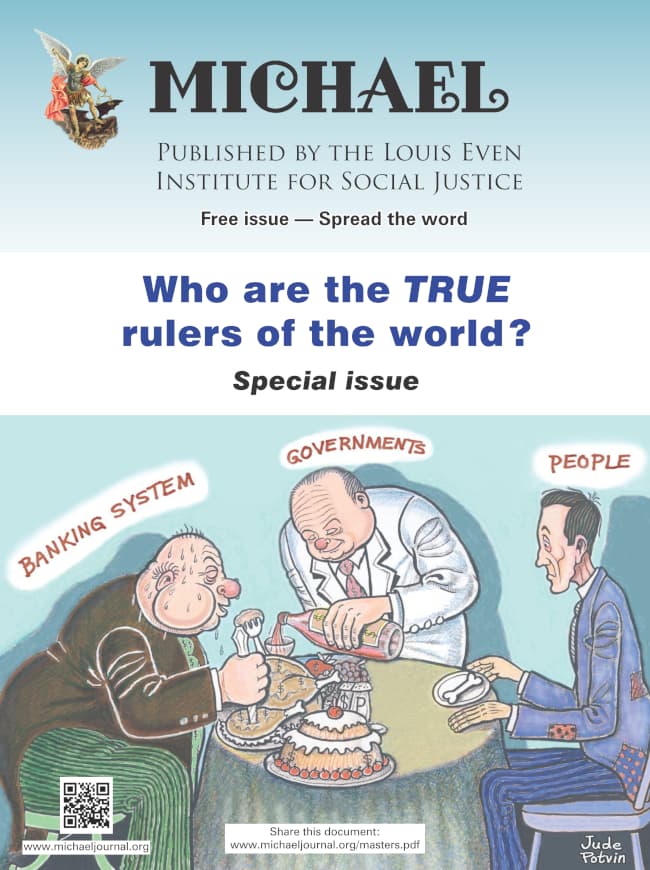

In this special issue of the journal, MICHAEL, the reader will discover who are the true rulers of the world. We discuss that the current monetary system is a mechanism to control populations. The reader will come to understand that "crises" are created and that when governments attempt to get out of the grip of financial tyranny wars are waged.

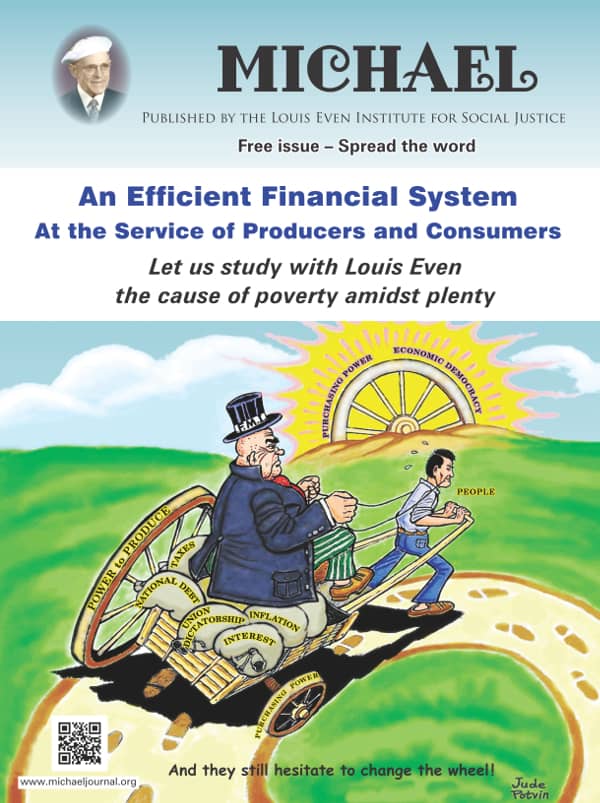

In this special issue of the journal, MICHAEL, the reader will discover who are the true rulers of the world. We discuss that the current monetary system is a mechanism to control populations. The reader will come to understand that "crises" are created and that when governments attempt to get out of the grip of financial tyranny wars are waged. An Efficient Financial System, written by Louis Even, is for the reader who has some understanding of the Douglas Social Credit monetary reform principles. Technical aspects and applications are discussed in short chapters dedicated to the three propositions, how equilibrium between prices and purchasing power can be achieved, the financing of private and public production, how a Social Dividend would be financed, and, finally, what would become of taxes under a Douglas Social Credit economy. Study this publication to better grasp the practical application of Douglas' work.

An Efficient Financial System, written by Louis Even, is for the reader who has some understanding of the Douglas Social Credit monetary reform principles. Technical aspects and applications are discussed in short chapters dedicated to the three propositions, how equilibrium between prices and purchasing power can be achieved, the financing of private and public production, how a Social Dividend would be financed, and, finally, what would become of taxes under a Douglas Social Credit economy. Study this publication to better grasp the practical application of Douglas' work.  Reflections of African bishops and priests after our weeks of study in Rougemont, Canada, on Economic Democracy, 2008-2018

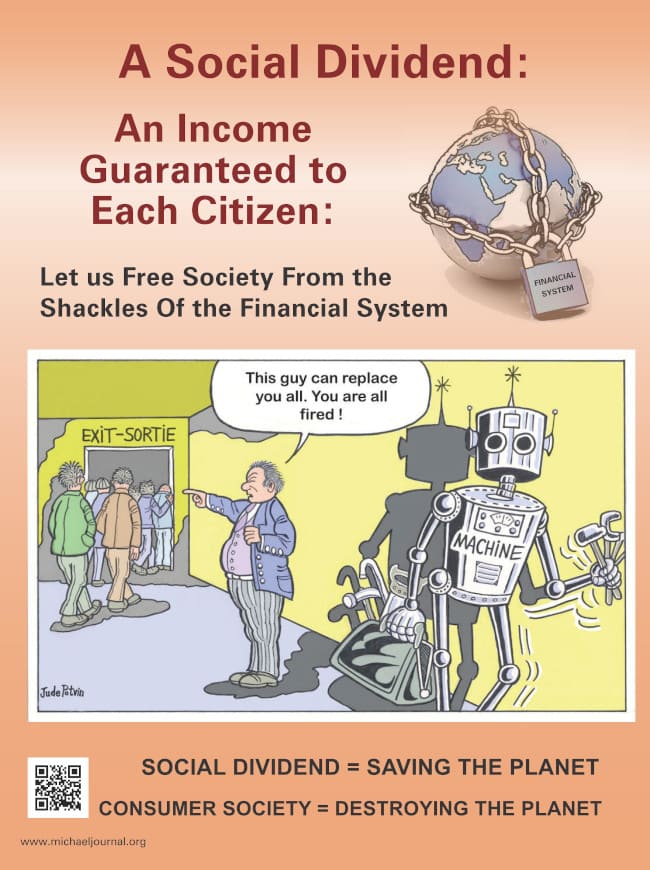

Reflections of African bishops and priests after our weeks of study in Rougemont, Canada, on Economic Democracy, 2008-2018 The Social Dividend is one of three principles that comprise the Social Credit monetary reform which is the topic of this booklet. The Social Dividend is an income granted to each citizen from cradle to grave, with- out condition, regardless of employment status.

The Social Dividend is one of three principles that comprise the Social Credit monetary reform which is the topic of this booklet. The Social Dividend is an income granted to each citizen from cradle to grave, with- out condition, regardless of employment status.Rougemont Quebec Monthly Meetings

Every 4th Sunday of every month, a monthly meeting is held in Rougemont.