Maclean's Magazine of December 19, 1959, carried an article by C. Knowlton Nash entitled, "Why don't we send our surplus food to the starving?" Below is quoted the opening section of this article, with certain paragraphs emphasized by us.

On a dusty side street in Chittagong town, Bengal, workers lifted the body of Krishnan Gupta, peasant, out of the gutter and dumped it on a cart. He had come into town looking for food. He died of starvation.

Five thousand miles west of Chittagong town, William Wesson, a United States Department of Agriculture employee was shovelling surplus wheat for storage aboard a "mothballed" "ship near Seattle.

The Asian peasant and the American: surplus shoveller symbolize today's greatest tragedy; the shocking spectacle of starving millions on one side of the globe and warehouses bulging with food surpluses over on the other side.

In India alone there are sixty million persons suffering at least semi-starvation. Sooner or later they will die because they did not get enough to eat. On our side of the world, reducing salons are doing a roaring business.

Simple logic cries out that the solution is to move the world's food surpluses into the world's hungry stomachs. But thousands of economists, politicians and international civil servants have spent the last half dozen years seeking and failing to find a way to do it that is acceptable to our frequently hard-hearted and occasionally soft-headed governments.

One appalling fact about this surplus problem is that while our taxes keep going to buy guns and missiles and hydrogen bombs, the West's greatest cold-war weapon, food, lies unused.

Most of the hungry people of this world are in Africa and Asia, target areas for Communism. An empty belly is an open invitation to Communism.

There is no one who can deny the truth of Mr. Knowlton Nash's statements. It is the scandal of our civilization to see so-called civilized countries pretending that they are stumped with the problem of getting rid of their food surpluses, while all the time a good half of the world's people are caught in the grip of starvation and undernourishment. And these "civilized" countries have at hand all the means necessary to transport these surpluses of food rapidly and efficiently to any part of the world where they may be needed.

Furthermore, the motive impelling the well-to-do countries to go to the aid of those poverty stricken should not be fear of Communism but rather respect for distributive justice.

Even if there were no Communist menace, even if the rich countries had no reason to fear for their liberty and their wealth, still the surpluses of those who have should go to fill the needs of those countries which have not. The riches of the earth were meant for all men. Regardless of the inequalities sources of production between countries, the goods which are produced should in some way be distributed to the end that every individual would have sufficient wherewith to meet his essential needs — and, mind you, our productive system is quite capable of attaining this end today.

But what stands in the way of realising this ideal? What is it that prevents excess stocks of foods being carried to hungry countries? What but purely financial considerations! These starving human beings haven't the wherewithal with which to pay for the surplus stocks of the glutted countries.

Nevertheless, if we admit that each one has a right to a share, that the surpluses of one should go to relieve the needs of the other, then there no longer remains any problem about buying and selling. You don't sell to some one that which is his just due: we simply hand it over to him.

But, alas! finance has come so to dominate the relationship between man and man and between entire peoples that principles are smothered and what is in fact monstrous comes to be accepted as the commonplace. We shudder when we read how humans were made sacrifices to Moloch and the Minotaur in the rites of ancient paganism. Yet we bow and worship and sacrifice to Mammon, the god of today, who counts his victims in the millions condemned to torture and death by starvation.

In his article, Knowlton Nash blames the governments for having "hard hearts and soft heads" in that they have not accepted any of the solutions which for the past ten years, have been proferred by those who have striven their utmost to find a solution. Rather we should blame the financiers who control the government for lack of a solution to this problem. And yet the governments must be severely censured for having allowed themselves to become the willing servants of financial interests and for consenting to continue to play this role in the face of the tragic situation which has developed among the underprivileged races of the earth.

It is not astonishing, however, that we have not been able to overcome this purely financial obstacle to distributing the surpluses of Canada and the United States to the peoples of India and Africa. After all we have not yet been able to vanquish the same obstacle which here at home prevents us from distributing some of these surpluses to our own needy people who are actually dwelling among these surpluses.

There are here in our own country of Canada — and in the United States as well — a vast number of families condemned to do without proper nourishment and many other necessities even though there is a superfluity of food and other goods lying in the stores and warehouses of the nation. These goods are not distributed for the same reason mentioned above — because those needing these goods cannot pay for them. Here is no problem of international finance. It's a problem of mere national finance.

When the government is asked to double family allowance rates so that the children of our homes might be able to benefit from the super abundant production of our country, the politicians and their economic advisers reply that if this were done it would be necessary to increase the taxes paid by the citizens.

When we speak of produce and products they think only of money. And note well, that here there is no question of taking from one in order to provide for the needs of another. We are speaking of surplus production, of a production system which is capable of producing even greater surpluses. There exists no mathematical contradiction in the suggestion that, instead of subtracting from one in order to add to another we simply add to that other and leave the one as it is when there is question of surpluses. But if you do make such a suggestion the bankers and the other economic solons will cast a cold regard upon you, and come back with the biting question: "Do you want to bring down upon us the catastrophe of inflation?"

Ask these distinguished gentlemen just what they mean by "inflation" and they'll give your without any hesitation, the hackneyed old response; "'Too much money chasing after too few goods." However, today we find just the opposite happening: too many goods solliciting an insufficiency of money. Still our distinguished financiers and their advisers will not budge from their position. Consequently families are condemned to live in want and need regardless of the fact that production is so abundant that it is causing unemployment.

And such thinking likewise condemns the Asiatic peoples to death by starvation or malnutrition while all the while our countries try desperately to find a means of getting their surplus production moving.

In considering the illogicalness, not to say the inhumanity, of this situation, we are inclined to agree with G. Lafond when he writes in La Grande Relève, that any war against hunger must be preceded by a war against stupidity. And this stupidity does not lie with the hungry nor with those who produce food. The stupidity is on the part of those who hold the reins of power in so-called civilized countries and on the part of their advisers who are bedecked with a bewildering array of degrees. The stupidity is exercised by those who find the existing financial system satisfactory and work to keep it operating.

As for the bankers and those who control.money and credit — they are not guilty of stupidity. Their crime is one of avarice, of greed, not only for money but perhaps much more for power in so-called civilized countries and on the life-blood of the economic body, for control in this fashion, over the nation, over families, over individuais even.

The solution which these distinguished economic scholars have been searching for during ten years in order to be able to distribute to consumers the goods for which, they have need, was presented to the world some forty years ago by a genius bearing the name, Douglas. The solution he presented, at once logic and humane, is called Social Credit.

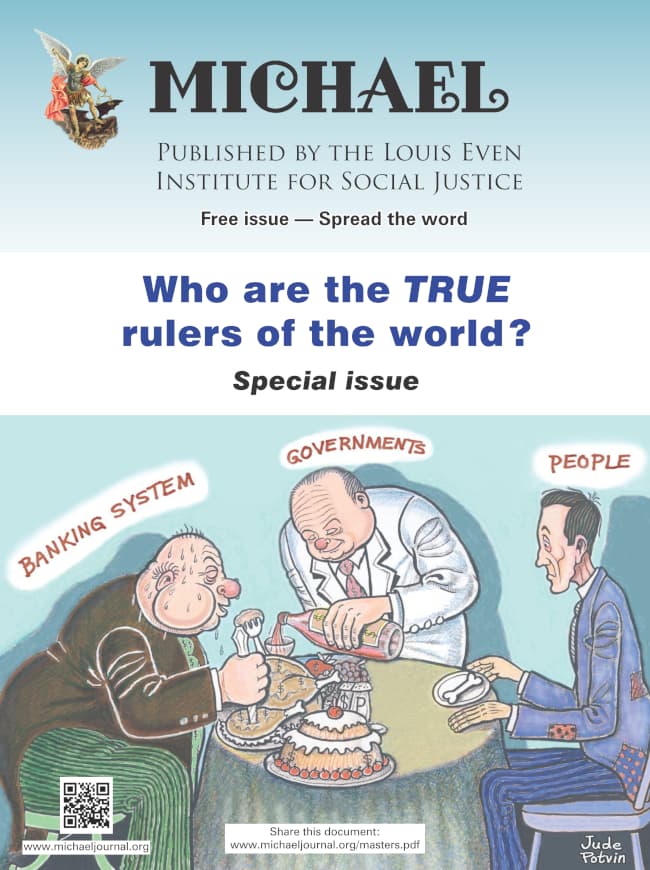

In this special issue of the journal, MICHAEL, the reader will discover who are the true rulers of the world. We discuss that the current monetary system is a mechanism to control populations. The reader will come to understand that "crises" are created and that when governments attempt to get out of the grip of financial tyranny wars are waged.

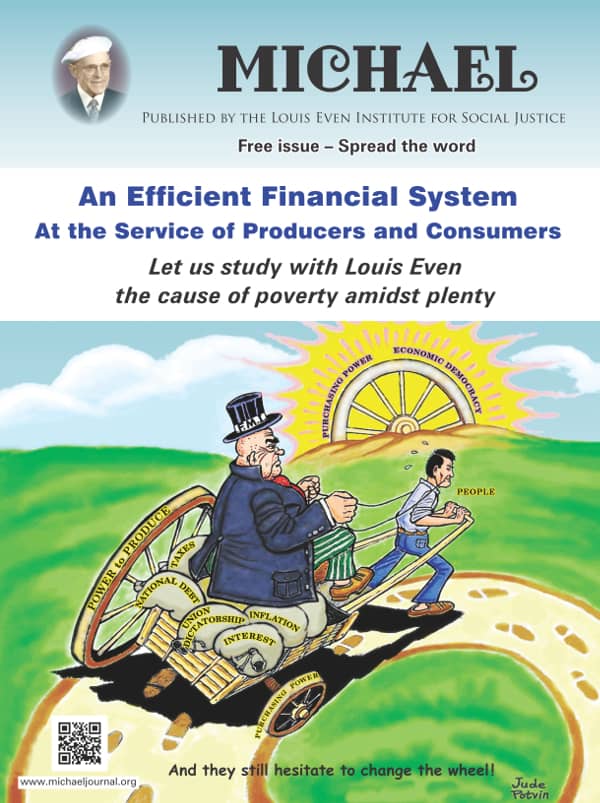

In this special issue of the journal, MICHAEL, the reader will discover who are the true rulers of the world. We discuss that the current monetary system is a mechanism to control populations. The reader will come to understand that "crises" are created and that when governments attempt to get out of the grip of financial tyranny wars are waged. An Efficient Financial System, written by Louis Even, is for the reader who has some understanding of the Douglas Social Credit monetary reform principles. Technical aspects and applications are discussed in short chapters dedicated to the three propositions, how equilibrium between prices and purchasing power can be achieved, the financing of private and public production, how a Social Dividend would be financed, and, finally, what would become of taxes under a Douglas Social Credit economy. Study this publication to better grasp the practical application of Douglas' work.

An Efficient Financial System, written by Louis Even, is for the reader who has some understanding of the Douglas Social Credit monetary reform principles. Technical aspects and applications are discussed in short chapters dedicated to the three propositions, how equilibrium between prices and purchasing power can be achieved, the financing of private and public production, how a Social Dividend would be financed, and, finally, what would become of taxes under a Douglas Social Credit economy. Study this publication to better grasp the practical application of Douglas' work.  Reflections of African bishops and priests after our weeks of study in Rougemont, Canada, on Economic Democracy, 2008-2018

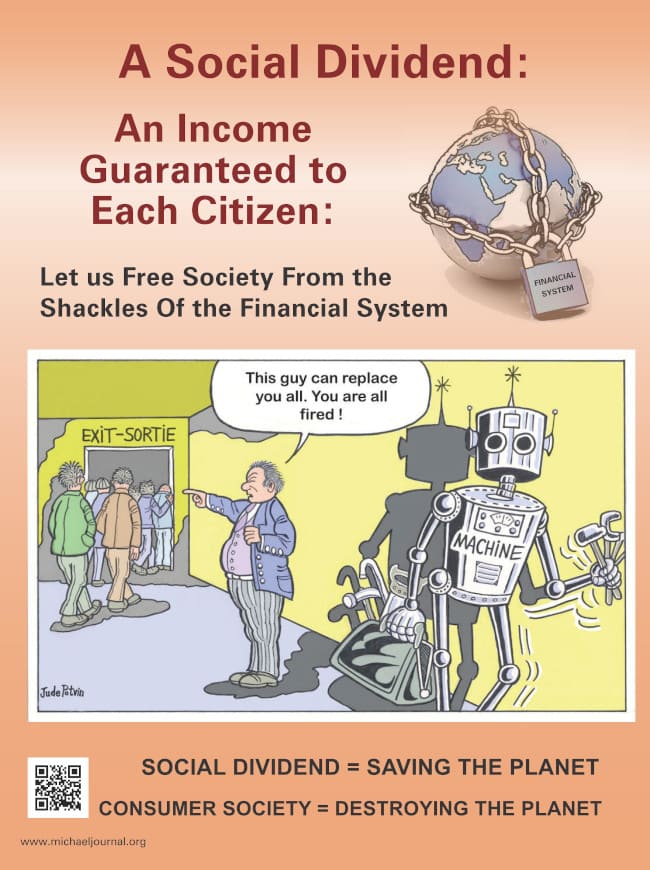

Reflections of African bishops and priests after our weeks of study in Rougemont, Canada, on Economic Democracy, 2008-2018 The Social Dividend is one of three principles that comprise the Social Credit monetary reform which is the topic of this booklet. The Social Dividend is an income granted to each citizen from cradle to grave, with- out condition, regardless of employment status.

The Social Dividend is one of three principles that comprise the Social Credit monetary reform which is the topic of this booklet. The Social Dividend is an income granted to each citizen from cradle to grave, with- out condition, regardless of employment status.Rougemont Quebec Monthly Meetings

Every 4th Sunday of every month, a monthly meeting is held in Rougemont.