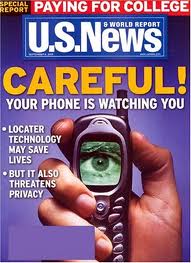

The September 8, 2003 issue of the weekly magazine U.S. News & World Report, in its cover story, published an article about cellphones, chips, and radio tags that are tracking people and things:

The September 8, 2003 issue of the weekly magazine U.S. News & World Report, in its cover story, published an article about cellphones, chips, and radio tags that are tracking people and things:

“The new location technology promises an array of benefits: emergency services that respond better, real-time driving directions to avoid traffic jams, and better-stocked store shelves offering cheaper goods. Still, the idea that cellphones and other goods can be trailed unsettles some people, and analogies to Big Brother are inevitable. Left unchecked, such technologies `will allow corporations or the Government to constantly monitor what individual Americans do every day,' the American Civil Liberties Union warned in a recent report. Wireless carriers say their systems only pinpoint callers if they've dialed 911 – or if they have explicitly agreed to be found. But privacy advocates say that the technology will inevitably generate data that a detective, or an angry spouse's divorce attorney, will demand in court. In short, the new phones, tags, and chips will keep you from ever getting lost. The nagging fear is that they'll let others find you, whether you like it or not. (...)

“In five or 10 years, the car seat itself – or the driver's shoe or sweater – may also have a chip that can be scanned by nearby readers. The world's largest retailer, Wal-Mart, created a stir this summer by saying it wanted crates and pallets of goods arriving at its warehouses in 2005 to carry radio frequency identification, or RFID, chips. The tags, which broadcast a burst of data when scanned with a radio signal, store much more detailed information than conventional bar codes, and can be read from up to 10 feet away. By making goods easier to identify and trace, the chips could cut waste, theft, and loss, and drastically streamline delivery, says retail consultant Scott Lundstrom of AMR Research. (...)

“Pets have them; soon products will too. So why not radio tags for people? A Florida-based company called Applied Digital Solutions is injecting a rice-grain-sized ID chip under the skin of a few willing pioneers, including a Florida family dubbed the ‘Chipsons.’ Acquaintances raised their eyebrows, says mom Leslie Jacobs, 47. ‘But people thought pacemakers were weird at first.’

“Privacy experts, however, are spooked by the idea that people's personal data could be scanned without their knowledge. They're even less comfortable with another Applied Digital Solutions implant, still a prototype, that would include a global positioning system chip, and could be tracked remotely.”