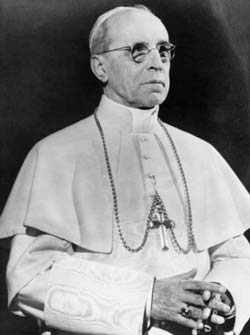

Pius XII, Pope from 1939 to 1958, “rescued more Jews than all the Allies combined.” Pius XII, Pope from 1939 to 1958, “rescued more Jews than all the Allies combined.” |

During and after World War II, and again upon his death in 1958, Pope Pius XII was praised by secular and Jewish leaders for his efforts to save Jews from the Nazi-induced Holocaust. During the last forty years, however, many people, including some Catholics, have accused the Pope of “silence” and even of criminal negligence, saying he could have said and done much more to lessen the genocide that claimed millions of Jews.

These attacks against Pius XII require a false rewriting of history that does not survive honest scrutiny. Because of a defamatory work of fiction, “The Deputy”, written in 1963 by a little-known German Protestant playwright, Rolf Hochhuth, Pius XII's wartime record has been unjustly tarnished. In this play, the main protagonist, the young Jesuit Riccardo Fontana, says: “A Vicar of Christ who sees these things before his eyes and still remains silent because of state policies, who delays even one day... such a pope is a criminal.” (Ironically, as a boy, Hochhuth was a member of the Hitler Youth, and his father, an officer in the German Army.)

Ever since the play by Hochhuth was staged, it has become part of conventional folklore to blame Pope Pius XII for being "silent" during the Holocaust. But that is certainly not what many were saying at the time, including the World Jewish Congress, the American Jewish Committee, Golda Meir, Albert Einstein, and many others — all of whom applauded the efforts of Pius XII to do what he could to save Jews. Mainly by providing false birth certificates, religious disguises, and safe keeping in cloistered monasteries and convents, the Pope oversaw efforts that helped save hundreds of thousands of Jews from deportation to Nazi death camps.

The Israeli diplomat and scholar Pinchas Lapide concluded his careful review of Pius XII's wartime activities with the following words: “The Catholic Church, under the pontificate of Pius XII, was instrumental in saving the lives of as many as 860,000 Jews from certain death at Nazi hands.” He went on to add that this “figure far exceeds those saved by all other Churches and rescue organizations combined.” After recounting statements of appreciation from a variety of preeminent Jewish spokespersons, he noted. “No Pope in history has been thanked more heartily by Jews.”

At the Eichmann Nazi War Crimes Trial in 1961, Jewish scholar Jeno Levai testified that the Bishops of the Catholic Church “intervened again and again on the instructions of the Pope.” In 1968, he wrote that “the one person (Pius XII) who did more than anyone else to halt the dreadful crime and alleviate its consequences, is today made the scapegoat for the failures of others.” In “The Secret War Against the Jews” in 1994, Jewish writers John Loftus and Mark Aarons write that “Pope Pius XII probably rescued more Jews than all the Allies combined.”

The Pope's efforts did not go unrecognized by Jewish authorities, even during the War. The Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem, Isaac Herzog, sent the Pope a personal message of thanks on February 28, 1944, in which he said: “The people of Israel will never forget what His Holiness and his illustrious delegates, inspired by the eternal principles of religion which form the very foundations of true civilization, are doing for us unfortunate brothers and sisters in the most tragic hour of our history, which is living proof of Divine Providence in this world.”

In September 1945, Dr. Joseph Nathan —who represented the Hebrew Commission —stated: “Above all, we acknowledge the Supreme Pontiff and the religious men and women who, executing the directives of the Holy Father, recognized the persecuted as their brothers and, with great abnegation, hastened to help them, disregarding the terrible dangers to which they were exposed.”

Dr. A. Leo Kubowitzki, secretary general of the World Jewish Congress, came to present “to the Holy Father, in the name of the Union of Israelitic Communities, warmest thanks for the efforts of the Catholic Church on behalf of Jews throughout Europe during the war.”

In 1958, at the death of Pope Pius XII, Golda Meir, then Israel's Minister of Foreign Affairs, delivered a eulogy on behalf of the nation of Israel to the United Nations, stating: “We share the grief of the world over the death of His Holiness Pius XII. During a generation of wars and dissensions, he affirmed the high ideals of peace and compassion. During the 10 years of Nazi terror, when our people went through the horrors of martyrdom, the Pope raised his voice to condemn the persecutors and to commiserate with their victims. The life of our time has been enriched by a voice which expressed the great moral truths above the tumults of daily conflicts. We grieve over the loss of a great defender of peace.”

Never were the Jews and the Vatican so close as during World War II. The Vatican was the only place on the continent where they had any friends. The great Jewish physicist, Albert Einstein, who himself barely escaped annihilation at Nazi hands, stated in Time Magazine (December 23, 1940): “Being a lover of freedom, when the Nazi Revolution came in Germany, I looked to the universities to defend it, but the universities were immediately silenced. Then I looked to the great editors of the newspapers, but they, like the universities, were silenced in a few short weeks. Then I looked to individual writers... they too were mute. Only the Church,” Einstein concluded, “stood squarely across the path of Hitler's campaign for suppressing the truth... I never had any special interest in the Church before, but now I feel great affection and admiration... and am forced thus to confess that what I once despised, I now praise unreservedly.”

Pius XII looks at the food that the Vatican prepared for war prisoners and refugees of all races and creeds, even for those in concentration camps in Germany. Pius XII looks at the food that the Vatican prepared for war prisoners and refugees of all races and creeds, even for those in concentration camps in Germany. |

Israele Anton Zolli, the Chief Rabbi of Rome during the German occupation, wrote: “Volumes could be written on the multiform works of Pius XII, and the countless priests, religious and laity who stood with him throughout the world during the war.”

“No hero,” he said, “in all of history was more militant, more fought against, none more heroic, than Pius XII in pursuing the works of true charity... and thus on behalf of all the suffering children of God. What the Vatican did will be indelibly and eternally engraved in our hearts... Priests and even high prelates did things that will forever be an honor to Catholicism.”

Zolli was so moved by the Pope's efforts that he became a devoted friend of Pius XII. He eventually converted to the Catholic Faith, and took for his baptismal name, in 1945, Eugenio, in honor of Eugenio Pacelli (Pius XII). Rabbi Zolli's daughter, the psychiatrist Myriam Zolli, has issued a strong defense of Pius XII. She said the Pope was in steady contact with her father, and he worked diligently to save Jews from persecution. In an interview in the Italian daily Il Giornale, she recalled her father's prediction that Pope Pius XII would become a scapegoat for the West's silence in the face of the Holocaust. She concluded that “the world's Jewish community owes him a great debt.”

As a papal envoy to Germany from 1917 to 1929, Vatican Secretary of State in the 1930's, and Pope during World War II, Pius XII established a clear record of supporting the Jewish people against the Nazis. Lapide wrote: “Of the 44 speeches which the Nuncio Pacelli had made on German soil between 1917 and 1929, at least 40 contained attacks on Nazism or condemnations of Hitler's doctrines.” By their own testimony, the Nazis knew they had an enemy, and Jewish leaders, a faithful ally in Pius XII. To maximize church efforts and minimize Nazi backlash, Pius XII modified his tactics during the war, but his pro-Jewish efforts continued unabated.

As Cardinal Pacelli, he drafted the famous papal encyclical, Mit Brennender Sorge (which means “with burning anxiety” i.e. about the Nazi threat to racial minorities and specifically the Jews), which denounced Nazi paganism, racism and anti-semitism. The document was smuggled into Germany in March, 1937, and read from all Catholic pulpits. The day after Pacelli's election as Pope (March 3, 1939), the Nazi newspaper, Berliner Morganpost, stated its position clearly: “The election of Cardinal Pacelli is not accepted with favor in Germany because he was always opposed to Nazism.”

In his 1942 Christmas message, Pius XII denounced the growing Holocaust. He cried out for the “hundreds of thousands who without any fault of their own, sometimes only by reason of their nationality or race, are marked down for death or progressive extinction."

The New York Times editorial (Dec. 25, 1942) was specific: “The voice of Pius XII is a lonely voice in the silence and darkness enveloping Europe this Christmas... He is about the only ruler left on the Continent of Europe who dares to raise his voice at all.” The Pope's Christmas message was also interpreted in the Gestapo report: “In a manner never known before... the Pope has repudiated the National Socialist New European Order [Nazism]. It is true, the Pope does not refer to the National Socialists in Germany by name, but his speech is one long attack on everything we stand for. Here he is clearly speaking on behalf of the Jews.”

Pius XII followed the Dutch Roman Catholic hierarchy's plan to name the Jews explicitly in their condemnation of Nazi deportations, and he intended to issue a similar statement himself. The Nazis threatened to arrest more Jews. The Dutch Reformed Church agreed not to protest openly, but the Roman Catholic hierarchy issued, in May 1943, their famous protest against the deportations. The Nazis then launched an all-out offensive against Jews (except those who had converted to the Dutch Protestant Reformed Church). Ironically, it was the Dutch hierarchy's letter of open condemnation which led to the arrest and execution of Saint Edith Stein, the Jewish Roman Catholic nun and philosopher.

The news of the increased persecution reached Pius XII. His own protest was due to go into L'Osservatore Romano (the Vatican newspaper) that very evening, but he had the draft burnt saying, “If the protest of the Dutch Bishops has cost the lives of 40,000 people, my intervention would take at least 200,000 people to their deaths.” Such was the result of openly naming the Jews; more death from vain gestures. There is no doubt that if Pius XII had made such a vain gesture, instead of saving more Jewish lives, he would then have been open to the criticism of having made the situation of Jews worse by vain and inopportune public statements. Those who now criticise him for not saying enough would then have attacked him for saying too much.

The Jewish historian Pinchas Lapide sums it up: “The saddest and most thought-provoking conclusion is that whilst the Catholic clergy of Holland protested more loudly, expressly and frequently against Jewish persecutions than the religious hierarchy of any other Nazi-occupied country, more Jews – some 11,000 or 79% of the total – were deported from Holland; more than anywhere else in the West.”

Thereafter, Pius XII adopted his policy of not naming the Jews explicitly. This was partly because of his experience of the diplomatic “deafness” of the allied governments, and partly because of his knowledge and experience of the increased persecution of Jews which followed the condemnatory statements made by the religious authorities. He devoted himself instead to the covert rescue operation to save Jewish lives.

The real question is, therefore, not what did the Pope say, but what did the Pope do? Actions speak louder than words. Papal policy in Nazi Europe was directed with an eye to local conditions. Hitler described himself as “a complete pagan”, and he regarded the Catholic Church as his greatest enemy, which he would destroy when he had the opportunity. Prince Sapicha, the Cardinal of Cracow in Poland, told the Pope, perfectly accurately, that if there were open public denunciations, Catholics and Jews would be massacred in Poland. It was better to try and rescue as many as possible through the religious houses, and allow the opposition army to build up.

Thousands of Jews — the figures run from 4,000 to 7,000 — were hidden, fed, clothed, and bedded in the 180 known places of refuge in Vatican City, churches and basilicas, Church administrative buildings, and parish houses. Unknown numbers of Jews were sheltered in Castel Gandolfo, the site of the Pope's summer residence, private homes, hospitals, and nursing institutions, and the Pope took personal responsibility for the care of the children of Jews deported from Italy.

Later, after the war was over, Pius XII received a large delegation of Roman Jews in the Vatican, and ordered that the Imperial Steps be opened for them to enter by. These steps were usually reserved for crowned Heads of State. The Pope received them in the Sistine Chapel and, seeing that his Jewish visitors felt uncomfortable in that place, he came down from his throne and warmly welcomed them, telling them to feel completely at home, saying, “I am only the Vicar of Christ, but you are His very kith and kin.” Such was his great love for the Jewish people, augmented by his knowledge of their terrible sufferings.

As Italian historian Monica Biffi wrote: “It is a real ‘cold war’ that Pius XII waged against Hitler.” One understands that in May, 1952, Pius XII was able to say: “What could we have done that we did not do?” Angelic pastor, master of truth, Pius XII has been a great Pope, filled with courage and wisdom; a Pope who is the glory of the Church, to whom we owe our admiration, our gratitude, and our prayer.