|

“The book Informe sobre la esperanza. Diálogo con el cardenal Gerhard Ludwig Müller was recently released in Spain, published by the Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, and will soon be available in Italian, English, French, German. The cardinal is interviewed by Carlos Granados, the director general of the publisher. “The title of the book borrows from that of the book-length interview that the prefect of the congregation for the doctrine of the faith at the time, Joseph Ratzinger, published in 1985 with a huge splash all over the world: The Ratzinger Report, in Spanish Informe sobre la fe. Müller not only has his teacher in Ratzinger and succeeded him in the same post, but he is also the one to whom the pope emeritus has entrusted the publication of all his theological works.“ Here are excerpts from this book: |

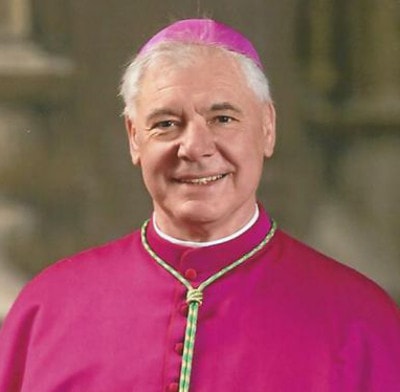

by Cardinal Gerhard L. Müller

Cardinal Gerhard L. Müller Cardinal Gerhard L. MüllerPrefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith |

The Church, with its magisterium, has the capacity to judge the morality of certain situations. This is a truth beyond question: God is the only judge who will judge us at the end of time, and the pope and bishops have the obligation to present the revealed criteria for this final judgment that is already anticipated today in our moral conscience.

The Church has always said “this is true, this is false,” and no one can interpret in a subjectivist way the commandments of God, the Beatitudes, the counsels, according to his own criteria, his own interest, or even his own needs, as if God were only the backdrop of his own autonomy. The relationship between the personal conscience and God is concrete and real, illuminated by the magisterium of the Church; the Church has the right and the obligation to declare that a doctrine is false, precisely because such a doctrine misleads ordinary people from the path that leads to God.

Pope Francis says in Evangelii Gaudium (no. 47) that the Eucharist “is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.” It is worthwhile to analyze this phrase in depth, in order not to misunderstand its meaning.

In the first place, it must be noted that this statement expresses the primacy of grace: conversion is not an autonomous act of man, but is, in itself, an action of grace. Nevertheless, it cannot be deduced from this that conversion is an external response of gratitude for what God has done in me on his own account, without me. Nor can I conclude that anyone may approach to receive the Eucharist even though he is not in the state of grace and with the appropriate dispositions, simply because it is nourishment for the weak.

First of all we must ask ourselves: what is conversion? It is a free act of man, and at the same time it is an act motivated by the grace of God, which always precedes the acts of men. This is why it is an integral act, incomprehensible if the action of God is separated from the action of man. […]

In the sacrament of penance, for example, one observes with absolute clarity the need for a free response on the part of the penitent, expressed in his contrition of heart, in his resolution to correct himself, in his confession of sins, in his act of penance. This is why Catholic theology denies that God does everything, and that man is a pure recipient of divine graces. Conversion is the new life that is given to us by grace, and at the same time it is also a task that is offered to us as a condition for perseverance in grace. […]

There are only two sacraments that constitute the state of grace: baptism and the sacrament of reconciliation. When someone has lost sanctifying grace, he needs the sacrament of reconciliation to recover this state, not as his own merit but as a gift, as a gift that God offers him in the sacramental form. Access to Eucharistic communion certainly presupposes the life of grace, it presupposes communion in the ecclesial body, it also presupposes an ordered life in keeping with the ecclesial body in order to be able to say “Amen.” Saint Paul insists on the fact that he who eats the bread and drinks the wine of the Lord unworthily will be guilty of the body and blood of the Lord (1 Cor 11:27).

St. Augustine affirms that “he who created you without you will not save you without you” (Sermon 169). God asks for my collaboration. A collaboration that is also his gift, but that implies my acceptance of this gift.

If things were different, we could fall into the temptation of conceiving of the Christian life in the manner of automatic realities. Forgiveness, for example, would become something mechanical, almost a demand, not a question that also depends on me, since I must realize it. I would then go to communion without the required state of grace and without approaching the sacrament of reconciliation. I would take it for granted, without any proof of this on the basis of the Word of God, that the forgiveness of my sins has been granted to me privately through this communion itself. But this is a false concept of God, it is tempting God. And it also brings with it a false concept of man, with an undervaluation of that which God can bring about within him.

The question of whether women’s priesthood is a disciplinary matter that the Church could simply change does not hold up, since this is a matter that has already been decided.

Pope Francis has been clear, just as his predecessors were. In this regard, I recall that Saint John Paul II, at no. 4 of the 1994 apostolic exhortation “Ordinatio Sacerdotalis,” reinforced with the royal plural (“declaramus”), in the only document in which that pope used this verb form, that it is a doctrine defined as infallibly taught by the ordinary universal magisterium (can. 750 § 2 CIC) that the Church has no authority to admit women to the priesthood.

It is up to the Magisterium to decide if a question is dogmatic or disciplinary; in this case, the Church has already decided that this proposal is dogmatic and that, being of divine law, it cannot be changed or even reviewed. This could be justified with many reasons, like fidelity to the example of the Lord or the normative character of the age-old practice of the Church, but I do not believe that this matter must be discussed again in depth, since the documents that deal with it sufficiently present the reasons to reject this possibility.

I do not want to fail to point out that there is an essential equality between man and woman on the level of nature, and also in relation with God through grace (cf. Gal 3:28). But the priesthood implies a sacramental symbolization of the relationship of Christ, head or bridegroom, with the Church, body or bride. Women can have, without any problem, many positions in the Church: in this regard, I gladly take the opportunity to thank publicly the large group of lay and religious women, some of them with specialized university degrees, who lend their indispensable collaboration in the congregation for the doctrine of the faith.

On the other hand, it would not be serious to advance proposals in this regard on the basis of mere human calculations, saying for example that “if we open the priesthood to women we will overcome the problem of vocations” or “if we accept women’s priesthood we would present a more modern image to the world.”

I believe that this way of presenting the debate is very superficial, ideological, and above all anti-ecclesial, because it neglects to say that this is a matter of a dogmatic question already defined by those who have the task of doing so, and not a merely disciplinary matter.