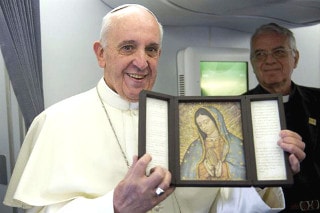

On February 12-17, 2016, Pope Francis made a pastoral journey to Mexico, and its culmination was most certainly the Holy Mass celebrated in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, where the Holy Father remained for 20 minutes in silent prayer in front of the miraculous image of the Virgin Mary. This was the main reason for his apostolic journey to Mexico, as he said in his first speech after his arrival in this country: “I come as a missionary of mercy and of peace but also as a son who wishes to pay homage to his mother, the Blessed Virgin of Guadalupe, and place himself under her watchful care.”

This long silent prayer impressed everybody, including journalists, who asked the Holy Father, during the in-flight press conference from Mexico to Rome, the reason for such a prayer, and what he had asked of the Virgin Mary. Pope Francis replied:

“I asked for the world, for peace. Many things… I asked forgiveness, I asked that the Church grow in health, I prayed on behalf of the Mexican people. And another thing I also asked wholeheartedly for was that priests be true priests, and nuns be true nuns, and bishops be true bishops: the way the Lord wants us to be. I asked this wholeheartedly. But other than that, the things a son says to his mother are somewhat secret…

“A people like this (the Mexicans) whose vitality persists can only be explained by Guadalupe. I invite you to seriously study the event of Guadalupe. Our Lady is there. I find no other explanation. It would be beautiful if you, as journalists.... There are already a few good books that explain, explain the painting as well, what it is like, what it means.... This way one can somewhat understand this people, so great, so beautiful.”

Studying this extraordinary story of the Apparition of the Virgin Mary in Mexico in 1531 is indeed worth the effort, since this Apparition was to be a turning point in the evangelization of the American continent. The following text is taken from the monthly spiritual newsletter of the Abbey of Clairval, France. It mentions Pope St. John Paul II, who visited the shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe four times: in 1979, 1990, 1999 and 2002—the last visit being for the canonization of Juan Diego, to whom the Virgin Mary had appeared.

One day as he was gazing at a copy of the Image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Pope St. John Paul II confided, “I feel drawn to this Image, because this face is full of tenderness and simplicity. It calls to me...” Later, on May 6, 1990, during a pilgrimage to Mexico, the Holy Father beatified Juan Diego, the messenger of Our Lady and, on this occasion, he said, “The Virgin chose Juan Diego, among the most humble, to receive this loving and gracious manifestation, the apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Her maternal face on the holy image that she left us as a gift is a permanent souvenir of this.”

One day as he was gazing at a copy of the Image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Pope St. John Paul II confided, “I feel drawn to this Image, because this face is full of tenderness and simplicity. It calls to me...” Later, on May 6, 1990, during a pilgrimage to Mexico, the Holy Father beatified Juan Diego, the messenger of Our Lady and, on this occasion, he said, “The Virgin chose Juan Diego, among the most humble, to receive this loving and gracious manifestation, the apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Her maternal face on the holy image that she left us as a gift is a permanent souvenir of this.”

In the sixteenth century, the Blessed Virgin, moved with pity for the Aztec people who, living in the darkness of idolatry, offered to their idols multitudes of human victims, deigned to take into her own hands the evangelization of these Indians of Central America who were also her children. One of the Aztec gods, originally considered the god of fertility, had transformed himself over time into a ferocious god. A symbol of the sun, this god was in continuous battle with the moon and the stars and was believed to need human blood to restore his strength; if he died, life would be extinguished. Ever new victims, to be offered to him in perpetual sacrifice, therefore seemed essential.

Aztec priests had prophesied that their nomadic people would settle in the place where an eagle would be seen perched on a cactus, devouring a serpent. This eagle appears on the Mexican flag today. Having arrived on a swampy island, in the middle of Lake Texcoco, the Aztecs saw the foretold sign: an eagle, perched on a cactus, was devouring a serpent. This was in 1369. There they founded their town Tenochtitlan, which would become Mexico City. The town expanded to become a city on pilings, with many gardens abounding in flowers, fruit, and vegetables. The organization of the Aztec kingdom was very structured and hierarchical. The knowledge of their mathematicians, astronomers, philosophers, architects, doctors, artists, and artisans was excellent for that time. But the laws of the physical world remained scarcely known. Tenochtitlan drew its power and wealth primarily from war. The conquered cities had to pay a tribute of various foodstuffs and men for war and sacrifices. The Aztecs’ human sacrifices and cannibalism are almost unequaled throughout the course of history.

|

| The Blessed Virgin Mary appeared to Juan Diego and talked to him in his native Aztec language, Nahuatl. She identified Herself as “Te-coa-tla-xope” (pronounced phonetically “te-quat-la-shupe) which in the Aztec tongue means “the one who crushes the head of the serpent”. For the Spanish, it sounded like Guadalupe, which was at that time a well-known Marian shrine in Spain. |

In 1474, a child was born who was given the name Cuauhtlatoazin (“speaking eagle”). After his father’s death, the child was taken in by his uncle. From the age of three, he was taught, as were all young Aztecs, to join in domestic tasks and to behave in a dignified manner. At school, he learned singing, dancing, and especially the worship of many gods. The priests had a very strong influence over the population, whom they kept in a submission bordering on terror. Cuauhtlatoazin was thirteen years old when the great temple at Tenochtitlan was consecrated. Over the course of four days, the priests sacrificed 80,000 human victims to their god. After his military service, Cuauhtlatoazin married a young woman of his social status. Together they led a modest life as farmers.

In 1519, the Spaniard Cortez disembarked in Mexico, leading 500 soldiers. He conquered the country for Spain, yet was not lacking in zeal for the evangelization of the Aztecs. In 1524 he obtained the arrival of twelve Franciscans to Mexico. These missionaries quickly integrated into the population. Their goodness contrasted with the harshness of the Aztec priests, as well as that of some conquistadors. They began to build churches. However, the Indians were reluctant to accept Baptism, primarily because it would require them to abandon polygamy.

Cuauhtlatoazin and his wife were among the first to receive Baptism, under the respective names of Juan Diego and Maria Lucia. After his wife’s death in 1529, Juan Diego withdrew to Tolpetlac, 14 km from Mexico City, to the home of his uncle, Juan Bernardino, who had become a Christian as well. On December 9, 1531, as was his custom every Saturday, he left very early in the morning to attend the Mass celebrated in honor of the Blessed Virgin, at the Franciscan fathers’ church, close to Mexico City. He walked past Tepeyac Hill. Suddenly, he heard a gentle and resounding song that seemed to come from a great multitude of birds. Raising his eyes to the top of the hill, he saw a white and radiant cloud. He looked around him and wondered if he was dreaming. All of a sudden, the song stopped and a woman’s voice, gentle and graceful, called him: “Juanito, Juan Dieguito!” He quickly climbed the hill and found himself in the presence of a very beautiful young woman whose garments shone like the sun.

Speaking to him in Nahuatl, his native language, she said to him, “Juanito, my son, where are you going?”—“Noble Lady, my Queen, I am going to the Mass in Mexico City to hear the divine things that the priest teaches us there.”—“I want you to know for certain, my dear son, that I am the perfect and always Virgin Mary, Mother of the True God from Whom all life comes, the Lord of all things, Creator of Heaven and Earth. I greatly desire that a church be built in my honor, in which I will show my love, compassion, and protection. I am your Mother full of mercy and love for you and all those who love me, trust in me, and have recourse to me. I will hear their complaints and I will comfort their affliction and their sufferings. So that I might show all My love, go now to the bishop in Mexico City and tell him that I am sending you to make known to him the great desire I have to see a church dedicated to me built here.”

Juan Diego went straight to the bishop. Bishop Zumárraga, a Franciscan, the first bishop of Mexico, was a pious man and full of zeal, who had a heart overflowing with kindness towards the Indians. He heard the poor man attentively, but fearing an illusion, did not put much faith in his story. Towards evening, Juan Diego started on his way home. At the top of Tepeyac Hill, he had the pleasant surprise of meeting the Apparition again. He told her about his mission, then added, “I beg you to entrust your message to someone more known and respected so that he will believe it. I am only a simple Indian whom you have sent as a messenger to an important person. Therefore, he didn’t believe me, and I do not want to greatly disappoint you.”—“My dearest son,” replied the Lady, “you must understand that there are many more noble men to whom I could have entrusted my message and yet, it is because of you that my plan will succeed. Return to the bishop tomorrow... Tell him that it is I myself, the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of God, who am sending you.”

On Sunday morning after the Mass, Juan Diego went to the bishop’s house. The prelate asked him many questions, then asked for a tangible sign of the truth of the Apparition. When Juan Diego went home, the bishop had him discreetly followed by two servants. At Tepeyac Bridge, Juan Diego disappeared from their sight, and despite all their searches on the hill and in the surrounding area, they could not find him again. Furious, they declared to the bishop that Juan Diego was an impostor who must absolutely not be believed. During this time, Juan Diego told the beautiful Lady, who was waiting for him on the hill, about his most recent meeting with the bishop. “Come back tomorrow morning to seek the sign he is asking for,” replied the Apparition.

|

| The shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City is the most visited Catholic shrine in the world, after the Vatican, with over 20 million visitors yearly. When the old basilica became dangerous due to the sinking of its foundations, a modern structure in the shape of a tent, called the New Basilica, was built next to it, in 1976; the original image of the Virgin of Guadalupe is now housed in this New Basilica, which can accommodate up to 10,000 people. |

Returning home, the Indian found his uncle ill, and the next day, he had to stay at his bedside to take care of him. As the illness got worse, the uncle asked his nephew to go look for a priest. At dawn on Tuesday, December 12, Juan Diego started on the road to the city. Approaching Tepeyac Hill, he thought it best to make a detour so as not to meet the Lady. But suddenly, he perceived her coming to meet him. Embarrassed, he explained his situation and promised to come back when he had found a priest to administer last rites to his uncle. “My dear little one,” replied the Apparition, “do not be distressed about your uncle’s illness, because he will not die from it. I assure you that he will get well... Go to the top of the hill, pick the flowers that you will see there, and bring them to me.” When he had arrived at the top of the hill, the Indian was stunned to find a great number of flowers in bloom, Castillian roses that gave off a very sweet fragrance. Indeed, in the winter, the cold allows nothing to survive, and besides, the place was too dry for flowers to grow there. Juan Diego gathered the roses, enfolded them in his cloak, or tilma, then went back down the hill. “My dear son,” said the Lady, “these flowers are the sign that you are to give the bishop... This will get him to build the church that I have asked of him.”

Juan Diego ran to the bishop. When he arrived, the servants made him wait for hours. Amazed at his patience, and intrigued by what he was carrying in his tilma, they finally informed the bishop, who, although with several people, had him shown in immediately. The Indian related his adventure, unfolded his tilma, and let the flowers, which were still shining with dew, scatter to the floor. With tears in his eyes, Bishop Zumárraga fell to his knees, admiring the roses from his native country.

|

| Juan Diego unfolds his tilma to show the flowers—and the miraculous image of Mary—to the bishop. |

All of a sudden, he perceived, on the tilma, the portrait of Our Lady. Mary’s image was there, as though printed on the cloak, very beautiful and full of gentleness. The bishop’s doubts gave way to a sure faith and a hope filled with wonder. He took the tilma and the roses, and placed them respectfully in his private oratory. The next day he went with Juan Diego to the hill where the apparitions had taken place. After having examined the sites, he let the seer return to his uncle’s house. Juan Bernardino had been completely cured. His cure had taken place at the very hour when Our Lady appeared to his nephew. He told him, “I have also seen her. She even came here and talked to me. She wants a church to be built on Tepeyac Hill and wants her portrait to be called ‘Saint Mary of Guadalupe.’ But she didn’t explain to me why.” The name “Guadalupe” is well known by the Spanish, because in their country there is a very old sanctuary dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe.

The news of the miracle spread quickly. In a short time, Juan Diego became well-known. “I will spread your fame,” Mary had told him, but the Indian remained as humble as ever. To make it easier to meditate on the Image, Bishop Zumárraga had the tilma transported to his cathedral. Then work was begun on the construction of a small church and a hermitage for Juan Diego on the hill of apparitions. The next December 25, the bishop consecrated his cathedral to the Most Blessed Virgin, to thank her for the remarkable favors with which she had blessed his diocese. Then, in a magnificent procession, the miraculous image was carried to the sanctuary that had just been completed on Tepeyac Hill.

To express their joy, the Indians shot arrows. One of them, shot carelessly, went through the throat of a participant in the procession, who fell to the ground, fatally wounded. A great silence fell and intense supplication rose to the Mother of God. Suddenly the wounded man, who had been placed at the foot of the miraculous image, collected himself and got up, full of vigor. The crowd’s enthusiasm was at its peak.

Juan Diego moved into his little hermitage, seeing to the maintenance and cleaning of the site. His life remained simple—he carefully farmed a field close to the sanctuary that had been placed at his disposal. He received pilgrims in ever larger numbers, and enjoyed talking about the Blessed Virgin and untiringly relating the details of the apparitions. He was entrusted with all kinds of prayer intentions. He listened, sympathized, and comforted. A good amount of his free time was spent in contemplation before the image of his Lady. He made rapid progress in the ways of holiness. Day after day, he fulfilled his duty as a witness up until his death on December 9, 1548, seventeen years to the exact day of the first apparition.

When the Indians had learned the news of Our Lady’s apparitions, an enthusiasm and joy such as had never been seen before spread among them. Renouncing their idols, superstitions, human sacrifices, and polygamy, many asked to be baptized. Nine years after the apparitions, nine million Indians had converted to the Christian faith—nearly 3,000 a day! The details of the Image of Mary moved the Indians deeply—this woman is greater than the sun-god since she appears standing before the sun. She surpasses the moon god since she keeps the moon under her feet. She is no longer of this world since she is surrounded by clouds and is held above the world by an angel. Her folded hands show her in prayer, which means that there is Someone greater than she...

Even in our time, the mystery of this miraculous image remains. The tilma, a large apron woven by hand from cactus fibers, bears the holy image, which is 1.43 meters tall. The Virgin’s face is perfectly oval and is a gray color verging on pink. Her eyes have a profound expression of purity and gentleness. The mouth seems to smile. The very beautiful face, similar to that of a mestizo Indian, is framed by a black head of hair that, up close, is comprised of silky locks. She is clad in a full tunic, of a pinkish red hue that no one has ever been able to reproduce, and that goes to her feet. Her bluish-green mantle is edged with gold braid and studded with stars. A sun of various shades forms a magnificent background, with golden rays shining out.

|

| The twisted bras crucifix after the blast of November 14, 1921. A bomb with 29 sticks of dynamite had been planted by Luciano Perez, a Spanish anarchist, in a flower arrangement on the altar under the tilma. |

The fact that the tilma has remained perfectly preserved from 1531 to this day is inexplicable. After more than four centuries, this fabric of mediocre quality retains the same freshness and the same lively color as when it was new. By comparison, a copy of the Image of Our Lady of Guadalupe painted in the 18th century with great care, and preserved under the same climatic conditions as Juan Diego’s, had completely deteriorated in a few years.

At the beginning of the 20th century, a painful period of revolutions in Mexico, a load of dynamite was put by unbelievers at the foot of the image, in a vase of flowers. The explosion destroyed the marble steps on the main altar, the candelabras, all the flower-holders. The marble altarpiece was broken into pieces, the brass Christ on the tabernacle was split in two. The windows in most of the houses near the basilica were broken, but the pane of glass that was protecting the Image was not even cracked. The image remained intact.

In 1936, an examination conducted on two fibers from the tilma, one red and the other yellow, led to an astounding finding—the fibers contained no known coloring agent. Ophthalmology and optics confirm the inexplicable nature of the image—it seems to be a slide projected onto the fabric. Closer analysis shows that there is no trace of drawing or sketching under the color, even though perfectly recognizable retouches were done on the original, retouches which moreover have deteriorated with time. In addition, the background never received any primer, which seems inexplicable if it is truly a painting, for even on the finest fabric, a coat is always applied, if only to prevent the fabric from absorbing the painting and the threads from breaking the surface. No brush strokes can be detected. After an infrared analysis conducted on May 7, 1979, a professor from NASA wrote, “There is no way to explain the quality of the pigments used for the pink dress, the blue veil, the face and the hands, or the permanence of the colors, or the vividness of the colors after several centuries, during which they ordinarily should have deteriorated... Studying this image has been the most moving experience of my life.”

Astronomers have observed that all the constellations present in the heavens at the moment Juan Diego opened his tilma before Bishop Zumárraga on December 12, 1531, are in their proper place on Mary’s mantle. It has also been found that by imposing a topographical map of central Mexico on the Virgin’s dress, the mountains, rivers and principal lakes coincide with the decoration on this dress.

Ophthalmological tests have found that Mary’s eye is a human eye that appears to be living, and includes the retina, in which is reflected the image of a man with outstretched hands—Juan Diego. The image in the eye conforms to the known laws of optics, particularly to that which states that a well-lighted object can be reflected three times in an eye (Purkinje-Samson’s law). A later study allowed researchers to discover in the eye, in addition to the seer, Bishop Zumárraga and several other people present when the image of Our Lady appeared on the tilma. And the normal microscopic network of veins in the eyelids and the cornea of the Virgin’s eyes is completely recognizable. No human painter would have been able to reproduce such details.

Gynecological measurements have determined that the Virgin in the Image has the physical dimensions of a woman who is three months pregnant. Under the belt that holds the dress in place, at the very location of the embryo, a flower with four petals stands out—the Solar Flower, the most familiar of Aztec hieroglyphs, and which symbolized for them divinity, the center of the earth, heaven, time, and space. On the Virgin’s neck hangs a brooch, the center of which is decorated with a little cross, recalling the death of Christ on the Cross for the salvation of all mankind. Many other details of the Image of Mary form an extraordinary document for our age, which is able to observe them thanks to modern technology. Thus science, which has often been a pretext for unbelief, helps us today to give prominence to signs that had remained unknown for centuries and that science is unable to explain.

Mexico City legalized abortion on April 24, 2007. The same day, after a Mass in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe offered for the unborn children, a very intense light appeared suddenly on the tilma of Juan Diego. At the level of the womb, the light appeared like a shiny halo, in the shape of an Mexico City legalized abortion on April 24, 2007. The same day, after a Mass in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe offered for the unborn children, a very intense light appeared suddenly on the tilma of Juan Diego. At the level of the womb, the light appeared like a shiny halo, in the shape of an  embryo. It lasted for one hour and was photographed and filmed; the photos were inspected by engineer Luis Girault and were declared authentic. embryo. It lasted for one hour and was photographed and filmed; the photos were inspected by engineer Luis Girault and were declared authentic. |

The Image of Our Lady of Guadalupe bears a message of evangelization: the Basilica of Mexico is a center “from which flows a river of the light of the Gospel of Christ, spreading throughout the earth through the merciful Image of Mary” (John Paul II, December 12, 1981). In addition, through her intervention on behalf of the Aztec people, the Virgin played a role in saving innumerable human lives, and her pregnancy can be interpreted as a special appeal on behalf of unborn children and the defense of human life. This appeal has a burning relevance in our time, when threats against the lives of individuals and peoples, especially lives that are weak and defenseless, are widespread and becoming more serious.

The Second Vatican Council forcefully deplored crimes against human life: “All offenses against life itself, such as murder, genocide, abortion, euthanasia... all these and the like are criminal: they poison civilization; and they debase the perpetrators more than the victims and militate against the honor of the Creator” (Gaudium et spes, 27). Faced with these plagues, which are expanding as a result of scientific progress and technology, and which benefit from wide social consensus as well as legal recognition, let us call upon Mary with confidence. She is an “incomparable model of how life should be welcomed and cared for... Showing us her Son, she assures us that in Him the forces of death have already been defeated” (John Paul II, Evangelium vitæ, March 25, 1995, nos. 102, 105). “Death and life are locked in an incredible battle; the Author of life, having died, lives and reigns” (Easter Sequence).

Let us ask Saint Juan Diego, canonized by Pope John Paul II on July 31, 2002, to inspire us with a true devotion to our Mother of Heaven, for “Mary’s compassion extends to all those who appeal to her, even when this appeal is nothing more than a simple ‘Hail, Mary’ ” (Saint Alphonsus de Liguori).

Dom Antoine Marie, OSB

This article is reprinted with permission from the Abbey of Clairval, France, which every month publishes a spiritual newsletter on the life of a saint, in English, French, Italian, or Dutch. Their postal address: Dom Antoine Marie, Abbe, Abbaye Saint-Joseph de Clairval 21150 Flavigny sur Ozerain, France. Their website: http:// www.clairval.com.