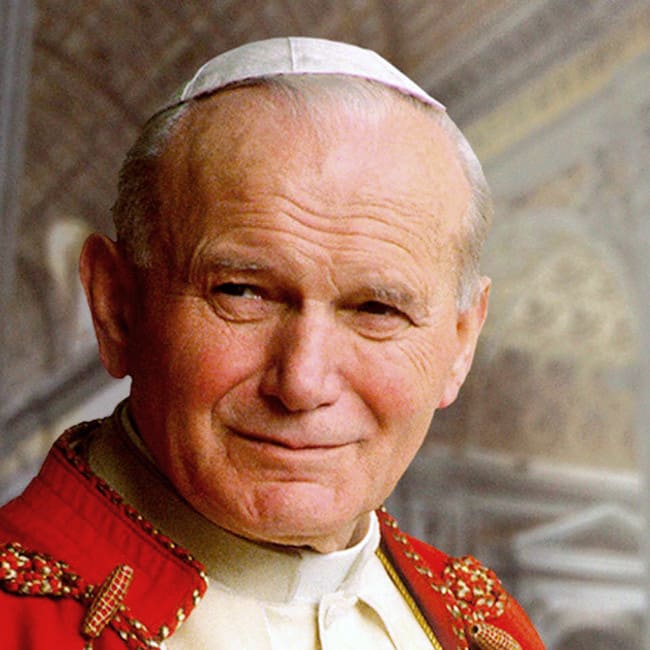

In December, 1984, St. Pope John Paul II issued the Apostolic Exhortation "Reconciliation and Penance," following the Synod of Bishops who gathered in Rome in 1983 on the theme "Reconciliation and Penance in the Mission of the Church". Although we are all sinners, and we all need God's forgiveness, these Bishops testified that they had witnessed an almost total abandonment of this sacrament by the faithful.

In December, 1984, St. Pope John Paul II issued the Apostolic Exhortation "Reconciliation and Penance," following the Synod of Bishops who gathered in Rome in 1983 on the theme "Reconciliation and Penance in the Mission of the Church". Although we are all sinners, and we all need God's forgiveness, these Bishops testified that they had witnessed an almost total abandonment of this sacrament by the faithful.

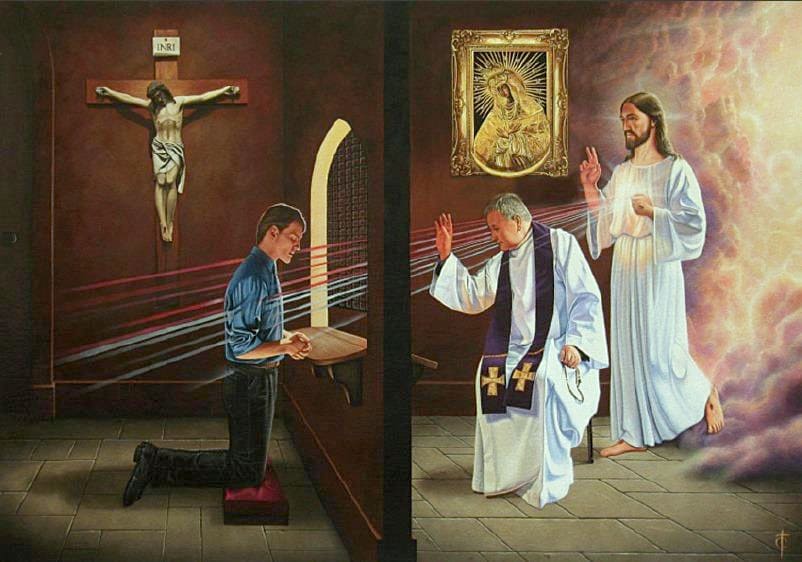

God's mercy infinitely exceeds all the sins of all men committed throughout human history; like the father in the parable of the prodigal son (Lk 15: 1-32), God is always ready to forgive us, but He cannot do it without our consent, without being asked, without ourselves truly regretting our mortal sins. And this can be done, as taught by the Church, only in the sacrament of Confession, also called the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation, by confessing one's sins to a priest.

What would be the status of a person who did not have a bath for 40 years, 50 years? He would definitely stink. Well, one can say the same thing from a spiritual point of view, about a person who did not go to confession for 40 or 50 years: this soul is in great need of being washed and purified by the blood of Jesus in the sacrament of forgiveness.

For this extraordinary Holy Year of Mercy, Pope Francis asked everyone to return to the sacrament of confession, and this will change the face of the world. Here we quote excerpts from the Apostolic Exhortation of St. John Paul II (no. 28 to 31), which reminds us of the main elements of this sacrament:

“The individual and integral confession of sins with individual absolution constitutes the only ordinary way in which the faithful who are conscious of serious sin are reconciled with God and with the Church.

– Saint John Paul II

The sacrament of penance is in crisis. The synod took note of this crisis. It recommended a more profound catechesis, but it also recommended a no less profound analysis of a theological, historical, psychological, sociological and juridical character of penance in general and of the sacrament of penance in particular. In all of this the synod's intention was to clarify the reasons for the crisis and to open the way to a positive solution for the good of humanity. Meanwhile, from the synod itself the Church has received a clear confirmation of its faith regarding the sacrament which gives to every Christian and to the whole community of believers the certainty of forgiveness through the power of the redeeming blood of Christ.

It is good to renew and reaffirm this faith at a moment when it might be weakening, losing something of its completeness or entering into an area of shadow and silence, threatened as it is by the negative elements of the above-mentioned crisis. For the sacrament of confession is indeed being undermined, on the one hand by the obscuring of the mortal and religious conscience, the lessening of a sense of sin, the distortion of the concept of repentance and the lack of effort to live an authentically Christian life. And on the other hand, it is being undermined by the sometimes widespread idea that one can obtain forgiveness directly from God, even in a habitual way, without approaching the sacrament of reconciliation. A further negative influence is the routine of a sacramental practice sometimes lacking in fervor and real spontaneity, deriving perhaps from a mistaken and distorted idea of the effects of the sacrament.

It is therefore appropriate to recall the principal aspects of this great sacrament.

In the fullness of time the Son of God, coming as the lamb who takes away and bears upon himself the sin of the world, appears as the one who has the power both to judge and to forgive sins, and who has come not to condemn but to forgive and save.

Now this power to "forgive sins" Jesus confers through the Holy Spirit upon ordinary men, themselves subject to the snare of sin, namely his apostles: "Receive the Holy Spirit. Whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven; whose sins you shall retain, they are retained." ( Jn 20:22; Mt 18:18.)

This is one of the most awe-inspiring innovations of the Gospel! He confers this power on the apostles also as something which they can transmit–as the Church has understood it from the beginning–to their successors, charged by the same apostles with the mission and responsibility of continuing their work as proclaimers of the Gospel and ministers of Christ's redemptive work.

Here there is seen in all its grandeur the figure of the minister of the sacrament of penance who by very ancient custom is called the confessor.

Just as at the altar where he celebrates the Eucharist and just as in each one of the sacraments, so the priest, as the minister of penance, acts "in persona Christi" The Christ whom he makes present and who accomplishes the mystery of the forgiveness of sins is the Christ who appears as the brother of man, the merciful high priest, faithful and compassionate, the shepherd intent on finding the lost sheep, the physician who heals and comforts, the one master who teaches the truth and reveals the ways of God, the judge of the living and the dead, who judges according to the truth and not according to appearances.

I cannot but recall with devout admiration those extraordinary apostles of the confessional such as St. John Nepomucene, St. John Vianney, St. Joseph Cafasso and St. Leopold of Castelnuovo, to mention only the best-known confessors whom the Church has added to the list of her saints. But I also wish to pay homage to the innumerable host of holy and almost always anonymous confessors to whom is owed the salvation of so many souls who have been helped by them in conversion, in the struggle against sin and temptation, in spiritual progress and, in a word, in achieving holiness.

From the revelation of the value of this ministry and power to forgive sins, conferred by Christ on the apostles and their successors, there developed in the Church an awareness of the sign of forgiveness, conferred through the sacrament of penance. It is the certainty that the Lord Jesus himself instituted and entrusted to the Church–as a gift of his goodness and loving kindness to be offered to all–a special sacrament for the forgiveness of sins committed after baptism.

As an essential element of faith concerning the value and purpose of penance, it must be reaffirmed that our savior Jesus Christ instituted in his Church the sacrament of penance so that the faithful who have fallen into sin after baptism might receive grace and be reconciled with God.

The truths mentioned above, powerfully and clearly confirmed by the synod and contained in the propositions, can be summarized in the following convictions of faith, to which are connected all the other affirmations of the Catholic doctrine on the sacrament of penance.

I. The first conviction is that for a Christian the sacrament of penance is the primary way of obtaining forgiveness and the remission of serious sin committed after baptism. Certainly the Savior and his salvific action are not so bound to a sacramental sign as to be unable in any period or area of the history of salvation to work outside and above the sacraments.

But in the school of faith we learn that the same Savior desired and provided that the simple and precious sacraments of faith would ordinarily be the effective means through which his redemptive power passes and operates. It would therefore be foolish, as well as presumptuous, to wish arbitrarily to disregard the means of grace and salvation which the Lord has provided and, in the specific case, to claim to receive forgiveness while doing without the sacrament which was instituted by Christ precisely for forgiveness.

II. The second conviction concerns the function of the sacrament of penance for those who have recourse to it. According to the most ancient traditional idea, the sacrament is a kind of judicial action; but this takes place before a tribunal of mercy rather than of strict and rigorous justice, which is comparable to human tribunals only by analogy, namely insofar as sinners reveal their sins and their condition as creatures subject to sin; they commit themselves to renouncing and combating sin; accept the punishment (sacramental penance) which the confessor imposes on them and receive absolution from him.

But as it reflects on the function of this sacrament, the Church's consciousness discerns in it, over and above the character of judgment in the sense just mentioned, a healing of a medicinal character. And this is linked to the fact that the Gospel frequently presents Christ as healer (Cf Lk 5:31). while his redemptive work is often called, from Christian antiquity, medicina salutis (medicine of salvation).

Whether as a tribunal of mercy or a place of spiritual healing, under both aspects the sacrament requires a knowledge of the sinner's heart in order to be able to judge and absolve, to cure and heal. Precisely for this reason the sacrament involves on the part of the penitent a sincere and complete confession of sins. This therefore has a raison d'etre not only inspired by ascetical purposes (as an exercise of humility and mortification), but one that is inherent in the very nature of the sacrament.

III. The third conviction, which is one that I wish to emphasize, concerns the realities or parts which make up the sacramental sign of forgiveness and reconciliation. Some of these realities are acts of the penitent, of varying importance but each indispensable either for the validity, the completeness or the fruitfulness of the sign.

First of all, an indispensable condition is the rectitude and clarity of the penitent's conscience. People cannot come to true and genuine repentance until they realize that sin is contrary to the ethical norm written in their in-most being; until they admit that they have had a personal and responsible experience of this contrast; until they say not only that "sin exists" but also "I have sinned"; until they admit that sin has introduced a division into their consciences which then pervades their whole being and separates them from God and from their brothers and sisters.

The sacramental sign of this clarity of conscience is the act traditionally called the examination of conscience, an act that must never be one of anxious psychological introspection, but a sincere and calm comparison with the interior moral law, with the evangelical norms proposed by the Church, with Jesus Christ himself, who is our teacher and model of life, and with the heavenly Father, who calls us to goodness and perfection.

But the essential act of penance, on the part of the penitent, is contrition, a clear and decisive rejection of the sin committed, together with a resolution not to commit it again, out of the love which one has for God and which is reborn with repentance. Understood in this way, contrition is therefore the beginning and the heart of conversion, of that evangelical metanoia which brings the person back to God like the prodigal son returning to his father, and which has in the sacrament of penance its visible sign and which perfects attrition. Hence "upon this contrition of heart depends the truth of penance."

While reiterating everything that the Church, inspired by God's word, teaches about contrition, I particularly wish to emphasize here just one aspect of this doctrine. It is one that should be better known and considered. Conversion and contrition are often considered under the aspect of the undeniable demands which they involve and under the aspect of the mortification which they impose for the purpose of bringing about a radical change of life.

But it is worthwile to recall and emphasize here the fact that contrition and conversion are even more a drawing near to the holiness of God, a rediscovery of one's true identity, which has been upset and disturbed by sin, a liberation in the very depth of self and thus a regaining of lost joy, the joy of being saved, which the majority of people in our time are no longer capable of experiencing.

We therefore understand why, from the earliest Christian times, in line with the apostles and with Christ, the Church has included in the sacramental sign of penance the confession of sins. This latter takes on such importance that for centuries the usual name of the sacrament has been and still is that of confession. The confession of sins is required, first of all, because the sinner must be known by the person who in the sacrament exercises the role of judge. He has to evaluate both the seriousness of the sins and the repentance of the penitent; he also exercises the role of the healer and must acquaint himself with the condition of the sick person in order to treat and heal him.

But the individual confession also has the value of a sign: a sign of the meeting of the sinner with the mediation of the Church in the person of the minister, a sign of the person's revealing of self as a sinner in the sight of God and the Church, of facing his own sinful condition in the eyes of God. The confession of sins therefore cannot be reduced to a mere attempt at psychological self-liberation even though it corresponds to that legitimate and natural need, inherent in the human heart, to open oneself to another. It is a liturgical act, solemn in its dramatic nature, yet humble and sober in the grandeur of its meaning. It is the act of the prodigal son who returns to his Father and is welcomed by him with the kiss of peace. It is an act of honesty and courage. It is an act of entrusting oneself, beyond sin, to the mercy that forgives.

Thus we understand why the confession of sins must ordinarily be individual not collective, just as sin is a deeply personal matter. But at the same time this confession in a way forces sin out of the secret of the heart and thus out of the area of pure individuality, emphasizing its social character as well, for through the minister of penance it is the ecclesial community, which has been wounded by sin, that welcomes anew the repentant and forgiven sinner.

The other essential stage of the sacrament of penance this time belongs to the confessor as judge and healer, a figure of God the Father welcoming and forgiving the one who returns: This is the absolution. The words which express it and the gestures that accompany it in the old and in the new Rite of Penance are significantly simple in their grandeur. The sacramental formula "I absolve you" and the imposition of the hand and the Sign of the Cross made over the penitent show that at this moment the contrite and converted sinner comes into contact with the power and mercy of God.

It is the moment at which, in response to the penitent, the Trinity becomes present in order to blot out sin and restore innocence. And the saving power of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus is also imparted to the penitent as the "mercy stronger than sin and offense," as I defined it in my encyclical Dives in Misericordia.

God is always the one who is principally offended by sin—"Tibi soli peccavi!" (against you alone I have sinned) and God alone can forgive. Hence the absolution that the priest, the minister of forgiveness, though himself a sinner, grants to the penitent is the effective sign of the intervention of the Father in every absolution and the sign of the "resurrection" from "spiritual death" which is renewed each time that the sacrament of penance is administered. Only faith can give us certainty that at that moment every sin is forgiven and blotted out by the mysterious intervention of the Savior.

Satisfaction is the final act which crowns the sacramental sign of penance. In some countries the act which the forgiven and absolved penitent agrees to perform after receiving absolution is precisely called the penance.

What is the meaning of this satisfaction that one makes or the penance that one performs? Certainly it is not a price that one pays for the sin absolved and for the forgiveness obtained: No human price can match what is obtained, which is the fruit of Christ's precious blood. Acts of satisfaction—which, while remaining simple and humble, should be made to express more clearly all that they signify—mean a number of valuable things: They are the sign of the personal commitment that the Christian has made to God in the sacrament to begin a new life (and therefore they should not be reduced to mere formulas to be recited, but should consist of acts of worship, charity, mercy or reparation).

They include the idea that the pardoned sinner is able to join his own physical and spiritual mortification—which has been sought after or at least accepted—to the passion of Jesus, who has obtained the forgiveness for him. They remind us that even after absolution there remains in the Christian a dark area due to the wound of sin, to the imperfection of love in repentance, to the weakening of the spiritual faculties. It is an area in which there still operates an infectious source of sin which must always be fought with mortification and penance. This is the meaning of the humble but sincere act of satisfaction. (...)

The synod repeated in one of its propositions the unchanged teaching which the Church has derived from the most ancient tradition, and it repeated the law with which she has codified the ancient penitential practice: The individual and integral confession of sins with individual absolution constitutes the only ordinary way in which the faithful who are conscious of serious sin are reconciled with God and with the Church. From this confirmation of the Church's teaching it is clear that every serious sin must always be stated, with its determining circumstances, in an individual confession.