by Louis Even

A few weeks ago, the Quebec Government announced that it ended its financial year with a $200-million deficit. This means that during the last year, the Government has spent 200 million dollars more than the Government has received through taxes. Of course, to be able to pay out more than it received through taxes, the Government had to borrow. The Opposition seized the occasion to admonish Jean Lesage’s Liberal Government for spending more than it has collected, and for driving the Province into debt.

There appears to be a double accusation made, two blames addressed to the Government: first, for having spent more than it received; second, for driving the Province into debt.

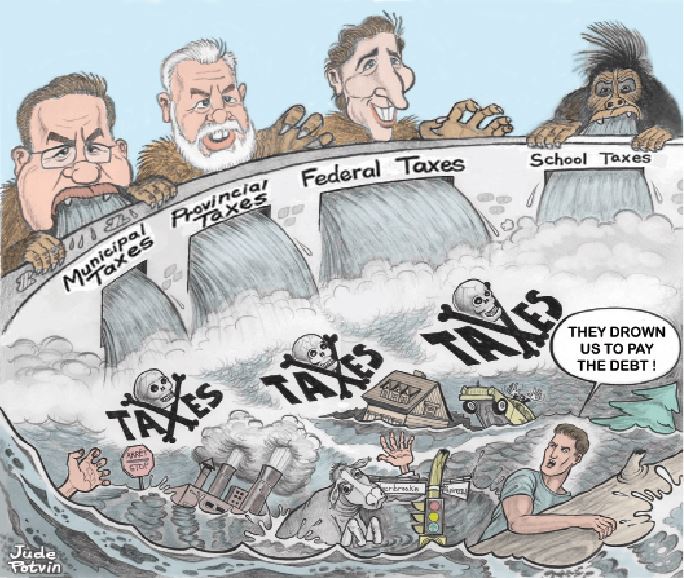

Must we condemn the Premier and his Government for having spent more than they received through taxes? No, we say, they did the right thing. Had they not spent this $200 million, there would have been $200 million less in services and works done for the population; therefore, there would have been more unemployment. And if the Government had drawn an extra $200 million in taxes to balance the budget, the population would have had $200 million less for its own use.

So, we can only congratulate the Government for having spent $200 million in goods for the Province without having taken these $200 million out of the taxpayers’ pockets.

— But, might it be argued, the Government has indebted the Province by as much, and taxes will have to be raised in the future, and these taxes will be greater since interests will be added, the loans will have to be paid back plus the interests.

— That is another matter. If we cannot, and if we must not blame the Lesage Government for having spent this $200 million, we can certainly blame it for having entered this amount as a provincial debt.

— Why blame it for having entered this amount as a provincial debt? It had no other choice, some will say.

— Why say they had no choice? What’s with this debt? What is it we owe? To whom do we owe it? Who owes this? What was this $200 million used for?

For many things. Let us say it was used to build roads, bridges, hospitals and some other things. Who built these roads, these bridges, the hospitals, and all these other things? Who built all of this?

They are people who were hired by the Government, who have received wages. They spent these wages, they bought food, clothing, they paid for their rent, etc.

Who made this food? Who made these clothes? Who built the houses? Again, the population of Quebec did, either one group of individuals, or another.

Yet, when all is said and done, it is the whole of the population that is considered to be in debt for $200 million, while it is the population as a whole who has made, who has produced goods to the amount of $200 million. Since when do we need to be indebted for something we ourselves have made?

This may sound odd since, as some would say, money had to be used to pay these people. Surely, they made the products but there was no money within the population to pay for these. What does this mean? Does it mean to say that the system of payment is not in tune with the production system? Is this normal?

We work, we make things, and we have no money to pay? Who does the work? Who makes the products? The people do. Who makes, who creates money? Neither the people nor the Government. Who makes money then? The financiers do, the bankers do. And we owe our roads to these people? They had no part in building the roads! And those who have built the roads, and everything else, it is they who owe the road to those who had no part in building it? Isn’t that absurd? Yes, supremely absurd.

What is even more absurd, is to demand that the price of these things be reimbursed, and that interest be added on top of it.

The $200 million were issued as credit, as money written in the banker’s ledger or through a similar channel.

What is money? Money are figures that are used to buy and to sell: Figures, whether they be written on paper bills, on metallic coins, in bankbooks, nothing more than figures. Figures had to be made, figures had to be found—$200 million in this case—to allow the people to produce.

These figures are the permission given, granted to the population to accomplish $200 million worth of public works. Isn’t it strange that the Government and the population should have to ask permission to make things that are useful to the Province, and that they should have to pay for this permission, and to pay interests upon this permission, and return all of this to the banker.

Such a system is not worth much; worst yet, it is an absurdity. And for the Government to admit such a system, such a state of affairs, is to forfeit its power to a power that has given itself, that has granted itself by this means, the right to control the country’s population and its Government.

And the same goes on outside of Quebec’s Provincial Government. The same applies to municipalities. Much is being said about the construction of the Montreal subway in the near future. Montreal’s mayor and his deputy mayor had to make several trips to Europe. What for? Undoubtedly to see different blueprints, the different ways to build a subway. But they also went to Europe looking for ways to finance their subway, to see whether they would borrow money from Paris, Brussels or London, rather than from New York, Montreal or Toronto, to build the metro.

This is not to say that if money is brought in from France, Belgium or England to build the Metro, the Metro will be built by Brits, or by Belgians, or by Frenchmen; it will still be built by Canadians. It will be built by Canadian workers, by Canadian engineers I gather—I doubt whether many will be invited from so far away for this purpose. And those who will be paid for this construction will be fed with food from our stores, with Canadian products, or with foreign products that have been exchanged for Canadian products. Therefore a subway will be built in Montreal using goods that belong to Canadians, and afterwards, to whom shall we pay this subway? To the British? To Belgians? To the French? Where is the logic in all of this?

Some will answer: “That’s the way the financial system works.” Yes, we know of course it is the financial system, but there is something wrong with all of this, that needs to be changed, to be corrected. Instead of allowing ourselves to be the slaves of the financial system, let us put the financial system at the service of reality.

Social Crediters have been saying this for years. They have gone so far as to ask the Federal Government: “Since we have a Bank of Canada—a bank said to be for Canadians, a bank which, according to its charter, must see to it that money, credit, be at the service of the country’s industry, of the country’s production—why force us then, to indebt ourselves towards financiers who profit from the people’s production, and who indebt the population for a production it has itself made?” Why not ask the Bank of Canada to issue, free of interest, all the money, all the financial credits needed to proceed to the performance of public works that can easily be executed and which are asked by the population. This applies to public financing, and public production, but could also be applied to the production of private goods.

Louis Even

Editor’s note: As it was explained in the March/April 2015 issue of MICHAEL, between 1939 and 1974, The Bank of Canada financed, without interest, as much as half of the country’s financial needs. (Even if the Bank of Canada were to charge a very small interest, this would be returned to the Canadian Government since it is the Bank’s only shareholder, making it the same as an interest-free loan.) The Government thus succeeded in financing several extensive public projects.

A change in policy was imposed in 1974 on the countries’ central banks by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS, the bank of central banks), based in Basel, Switzerland. Under the pretext that direct financing, free of interest, of a country by its own central bank might create inflation, it was recommended that countries be financed by private creditors, i.e. commercial banks. It is precisely from this time on that the debts of all Western countries began to grow exponentially.

In 1974, it was Pierre Elliott Trudeau who was Canada’s Prime Minister, and allowed this change of policy. Will his son Justin, now also Prime Minister, correct this wrong decision of his father?