Modern industry has made the huge working-class agglomerations to arise—what an author calls the barracks of the proletariat. Our nation has its great share of these barracks that one has erected with much enthusiasm, while paying homage to the foreign capital which at last deigned to enlist the sons and daughters of our native land.

Proletarians of pulp and paper-makers; proletarians of textiles; proletarians of mines; proletarians of asbestos; proletarians of aluminum; proletarians multiplied by the system of development of our natural resources to the benefit of international exploiters, no longer own a piece of land from which to derive their food, these former farmers or sons of former farmers have nothing, absolutely nothing, but what their wages can buy, to live and provide a living for their families.

From this moment on, the wage becomes the weapon by which an employer can manoeuvre his employees at will.

Just as the slave of old, today's wage-earner is not really free to accept or refuse the working conditions of the master, the employer.

No doubt, the worker can refuse to serve, or leave his employer. But, at the same time, bread leaves his table, and misery settles in at home.

No doubt, the worker can meet with his employer and expose his grievances to him, to prove how inadequate his wage is, in front of prices, to allow him, him and his own, a decent livelihood.

But is the employer much more independent than the worker?

The employer is not the absolute master of the enterprise. There is the financier who, year by year, demands that his money be fertile. From the very first day of its entrance into circulation, does not money lay claim to an offspring?

The employer's life already claims a profit. The fertility of money demands profits yet more peremptorily.

The first condition for industry to get profits is to sell its products. To sell, one must offer one's products at a price which can withstand other producers' competition. The worker can forget this, but the employer must keep it in mind constantly, or the threat of ruin violently reminds him of it.

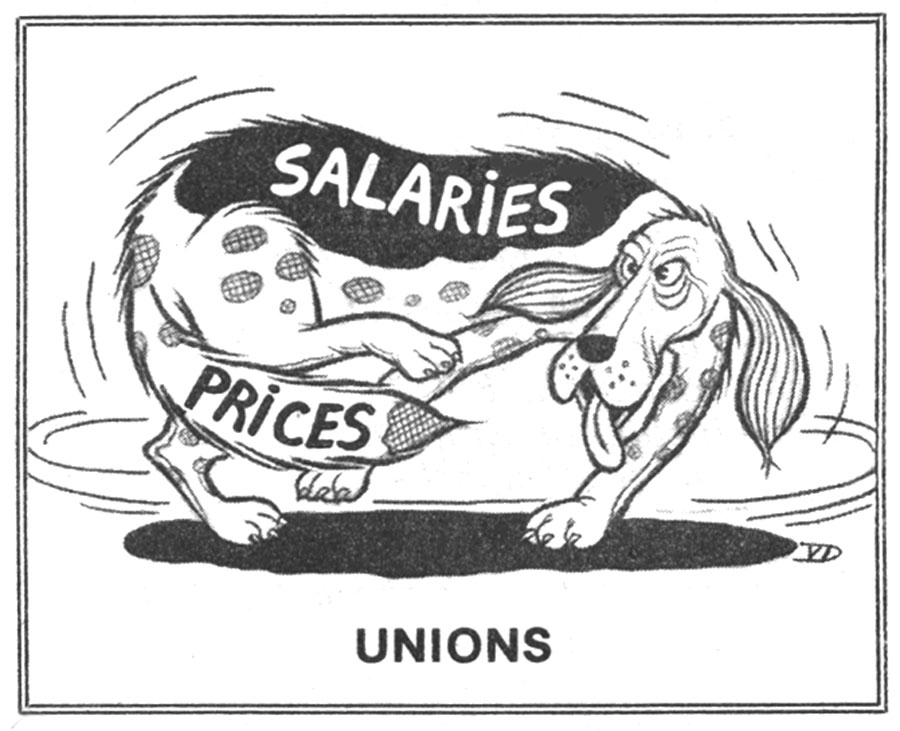

Now, if the employer increases his workers' wages, he must necessarily increase the sale price of his products—otherwise he will be in the red and have to consider a liquidation.

And if the employer increases his sale prices to cover wage increases, will he be able to sell in front of the competition? And if he does not sell, or if he sells less, he must reduce the number of his personnel, or sell at a loss and soon suffer the total closure of his workshops, putting both employers and employees in front of an empty chest, or to live off neighbours or public administrations.

No doubt all workers of an industry as a whole can unite to demand an increase in wages; no doubt, all employers of this industry as a whole can come to terms with one another, to agree to a general increase in wages and to a parallel increase in sale prices in this industry as a whole. The competition obstacle disappears by this cartel.

But what will be the result? Who will pay for the increase in sale prices, if not the consumer, who will have either to do without the more expensive items, or pay for them at the raised prices and do without other articles? In either case, at least short-time working will hit at least a section of the workers and employers.

The sectors which thus increase their wages and cover them by the price increases of their products, benefit temporarily. But in front of these increased prices, the other sectors will certainly bustle about until they get a corresponding increase. This is the general rise in prices that pinches all consumers. Now, do not the majority of the consumers belong to the working class?

What good does it do me to receive 5 percent more in wages, if the price of products is increased by 5 percent? Or if I have to be unemployed a day or two a week, or two to three months during the year?

And while the financiers, the entrepreneurs, and the employees are thus at daggers drawn with each other, to determine what share will go to one, what share to the other, mountains of products remain without buyers.

They strike back, unionize, mutually send out ultimatums, demand or refuse arbitration tribunals, discuss, put off, sign provisional agreements, outline them, begin the fights again, go on strike, declare lockouts, set up meetings, make virulent speeches. Hatred revives, moralists preach, agitators point out the shop windows and the beautiful homes, governments prepare to mobilize troops, masses turn toward Communism, investors are afraid, children die of hunger, women despair, men commit suicide, Christians are damned — all this because they do not manage to give satisfaction when they try to share out a two-billion dollar production, while at least two other billion worth of products vainly solicit consumers, and while other billions worth of goods could be made, if effective demand for them existed.

Three men fight to death over a loaf of bread, while two other loaves of bread rot under their very eyes, because no one thinks to take them.

The whole gamut of modern economic problems is there — the labour problem as well as the others: the emphasis in the economic question has been shifted from real wealth (products) — to the symbol (money). We tear each other to pieces on account of scarce money, instead of fraternizing to enjoy a plentiful production.

One thinks in terms of dollars, instead of thinking in terms of wheat, articles of clothing, shoes, houses, goods and services of all kinds. Because one thinks in terms of dollars, and because the banker makes the dollars scarce, one thinks in terms of scarcity.

It would be so easy to satisfy everybody, to establish peace and understanding between employers and workers, if the money to share was as plentiful as the offered production.

Would one need arbitration tribunals, or violent measures, to decide how many bushels of wheat, how many pounds of cheese, will be the employer's share and how many will be the worker's share, when the employers and workers together are incapable of consuming all the wheat and cheese that the country's even bridled production can provide?

Should one have to undergo so many struggles to decide how many pairs of shoes the employer will be able to appropriate and how many the worker will be able to take, when the shoe manufacturers have to close their doors because there are too many shoes in the country?

And this question could also be asked about firewood, space and material to build houses, furniture, and likewise, all other things.

There are ever so many resources to put plenty everywhere. But the distribution of all these things is tied to the money symbol. And one stops at the money symbol. One finds the money symbol scarce, and one accepts the decrees of those who make it scarce without reason. One does not see the plentiful things any more.

It is God and man's hands and minds that have made the plentiful things. One closes one's eyes to the generous gifts of Providence. One closes one's eyes to the fruits of man's genius and human labour, and one fixes them on the scarcity of money, and one persists obstinately to struggle for scarce money.

Therefore when are you going to open your eyes on the beautiful realities, instead of fastening them on the artificial symbols, you, sociologists, union leaders, who spend so much energy on the sharing of dollars?

If only you would devote one-tenth of these energies to demand that the dollar makers bring out dollars in relation to what the farmer brings out from his field, in relation to what the employer, the worker, and the machine bring out from the factory?

Make the Canadian dollars as plentiful as the Canadian production. Bring the Canadian dollars into the Canadian homes, to buy the Canadian production.

If the soil obeys the farmer's plough, if the tool obeys the mechanic, why should not the dollars obey an exact national accounting?

Then here a human mind, joining its personal researches to the researches and acquisitions of centuries of study, causes a new machine to come into existence. The machine will do the work of twenty workers and will require the attention of only one.

For the employer, it is an advantage. For the worker, it is a terror. Why? Since the machine supplies the product, while it does away with man's labour, and since the product is made for man, man ought to get the product in a different way than through his wages — at least in the proportion that the product comes without his labour.

A new problem is created for the worker — that of his displacement by the machine. This is a problem which will never be settled through wage scales, since the wage-earner is suppressed by mechanization.

What are the experts doing about the labour questions to bring to families the more and more plentiful production dissociated from human labour, dissociated from wages?

Trade unions organize and struggle. Why? Are not their activities wasted on the means of getting a bigger share of the scarce symbol, a bigger share of the dollars limited artificially in quantity? First of all, when have they considered demanding a total number of dollars regulated by total manual or mechanical production? Has not one seen frequently, on the contrary, the authorities of these trade unions eliminate attentively, or forbid formally, any discussion on this subject?

Money is scarce, they agree. The employer is, like themselves, the slave of money scarcity, they have to admit. But they accept this slavery, and they make use of their militancy in the struggle between slaves. They admit the artificial scarcity, and fight over rations.

To request the liberation of plenty would mean to give in to Social Credit; it would mean to become a political activist, according to them!

Accepting the absurd scarce money system in front of a plentiful production, is not being a political activist, but it is to call for a more accurate and more social system: this is being a political activist. Crawling is not being a political activist, but standing up to an unbelievable disorder: this is being a political activist. Taking from brothers who suffer equally from money scarcity, is not being a political activist, but attacking the bankers' system, which without reason creates this money scarcity: this is being a political activist.

Does not the master of money find remarkable protectors, even among those who seem to feel pity for his victims?

| Previous chapter - The Public-Debt Problem | Next chapter - There Is No Unemployment Problem |